Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning and F-22 'Raptor' : News & Discussion

- Thread starter Nick

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pourquoi l’Espagne renonce au F-35 et déclenche la colère noire de Washington

Why Spain is abandoning the F-35 and triggering Washington's wrath

By rejecting the F-35, Madrid is abandoning a key market for Washington and betting on European defence, even if it means straining its relations with the United States. - Credit:Elias Neil Benleulmi/SIPA / SIPA / Elias Neil Benleulmi/SIPA

On 6 August 2025, Madrid made its decision: there will be no American F-35s in its hangars. This public decision, which buries a €6.25 billion contract included in the 2023 budget for the purchase of new fighter jets, deprives Washington of a strategic market in Southern Europe.

The abandonment of the F-35 is part of Spain's ‘industrial and technological plan for security and defence’, which has recently been revised upwards with €10.5 billion in investments. Of these funds, 85% will be reinvested in European projects, notably in the future SCAF (Future Combat Air System).

The Spanish Navy, which was counting on the American aircraft to replace its AV-8B Harriers, and the Air Force, which was looking for a successor to its F/A-18 Hornets, must now reconsider their options. Dassault's NATO-certified Rafale F5 appears to be a serious contender.

Madrid breaks ranks over the 5% of GDP rule

Spain's choice is not limited to an arms purchase: it is part of a political standoff with Washington. Last June, at the NATO summit, Madrid refused to align itself with the collective commitment of member states to invest 5% of their GDP in military spending by 2035. Pedro Sánchez's government will stick to 2% this year, arguing that the effort is already significant for its economy.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Why Spain is abandoning the F-35 and triggering Washington's wrath

By rejecting the F-35, Madrid is abandoning a key market for Washington and betting on European defence, even if it means straining its relations with the United States. - Credit:Elias Neil Benleulmi/SIPA / SIPA / Elias Neil Benleulmi/SIPA

On 6 August 2025, Madrid made its decision: there will be no American F-35s in its hangars. This public decision, which buries a €6.25 billion contract included in the 2023 budget for the purchase of new fighter jets, deprives Washington of a strategic market in Southern Europe.

The abandonment of the F-35 is part of Spain's ‘industrial and technological plan for security and defence’, which has recently been revised upwards with €10.5 billion in investments. Of these funds, 85% will be reinvested in European projects, notably in the future SCAF (Future Combat Air System).

The Spanish Navy, which was counting on the American aircraft to replace its AV-8B Harriers, and the Air Force, which was looking for a successor to its F/A-18 Hornets, must now reconsider their options. Dassault's NATO-certified Rafale F5 appears to be a serious contender.

Madrid breaks ranks over the 5% of GDP rule

Spain's choice is not limited to an arms purchase: it is part of a political standoff with Washington. Last June, at the NATO summit, Madrid refused to align itself with the collective commitment of member states to invest 5% of their GDP in military spending by 2035. Pedro Sánchez's government will stick to 2% this year, arguing that the effort is already significant for its economy.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Un scandale d’Etat nommé F-35

A state scandal called F-35

From the Mirage affair to the purchase of the F-35, history is repeating itself. This time, however, parliament was informed and could have taken action to question a problematic choice in view of its additional costs, possible delays and Switzerland's strategic needs in terms of its neutrality.

Who will be held accountable? The Federal Council, the military administration, parliament? Because the affair looks very much like a ‘fiasco’, as the SVP has denounced. At the end of June, the Federal Council explained that the purchase of 36 F-35As would cost up to CHF 1.35 billion extra, even though no aircraft had yet been delivered.

The Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS) reported a ‘misunderstanding’ with Washington over a CHF 6 billion contract “understood” as a ‘fixed price’, which was immediately questioned by the Swiss Federal Audit Office. As for the date of the first deliveries, confirmed for 2027, this actually refers to the provision of eight aircraft at a military base in the United States. These will not be transferred to Switzerland until 2029.

Other additional costs, which have so far been minimised by Bern, could be added. According to the Canadian authorities, the upgrade of the F-35A (Block 4) that Switzerland will also have to carry out would cost between 20 and 30 million dollars extra per aircraft, or 720 million to 1.08 billion dollars in total.

While Bern has allocated CHF 120 million to bring its three military airports up to US standards, other countries have spent between $500 million and $600 million per airport. Bern has announced a new budget of CHF 60 million, no more.

A state scandal called F-35

From the Mirage affair to the purchase of the F-35, history is repeating itself. This time, however, parliament was informed and could have taken action to question a problematic choice in view of its additional costs, possible delays and Switzerland's strategic needs in terms of its neutrality.

Who will be held accountable? The Federal Council, the military administration, parliament? Because the affair looks very much like a ‘fiasco’, as the SVP has denounced. At the end of June, the Federal Council explained that the purchase of 36 F-35As would cost up to CHF 1.35 billion extra, even though no aircraft had yet been delivered.

The Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS) reported a ‘misunderstanding’ with Washington over a CHF 6 billion contract “understood” as a ‘fixed price’, which was immediately questioned by the Swiss Federal Audit Office. As for the date of the first deliveries, confirmed for 2027, this actually refers to the provision of eight aircraft at a military base in the United States. These will not be transferred to Switzerland until 2029.

Other additional costs, which have so far been minimised by Bern, could be added. According to the Canadian authorities, the upgrade of the F-35A (Block 4) that Switzerland will also have to carry out would cost between 20 and 30 million dollars extra per aircraft, or 720 million to 1.08 billion dollars in total.

While Bern has allocated CHF 120 million to bring its three military airports up to US standards, other countries have spent between $500 million and $600 million per airport. Bern has announced a new budget of CHF 60 million, no more.

I should just copy paste this,,"Some political noise, but let's just see what they buy"

India has already announced that the canceling of US stuff isn't true

timesofindia.indiatimes.com

timesofindia.indiatimes.com

So going by what you said, the Rafale F3 is easily updated to F5, which is what is going into the FCAS,,So FCAS if it goes ahead, which is doubtful, Is just a polished F3, Or are you just fabricating a story for the Indian forum again? There was talk of major changes

France is repeating history with the Eurofighter, have a dummy spit because you didn't get all of the work share,,,Go it alone with what you have,,,The Rafale was a polished Mirage

India has already announced that the canceling of US stuff isn't true

'No pause in talks related to buying US arms': Centre clarifies, pans 'false & fabricated' report - Times of India

India Business News: The defence ministry has refuted reports suggesting India halted defense purchase talks with the US, labeling them as false. This response follows a R

So going by what you said, the Rafale F3 is easily updated to F5, which is what is going into the FCAS,,So FCAS if it goes ahead, which is doubtful, Is just a polished F3, Or are you just fabricating a story for the Indian forum again? There was talk of major changes

France is repeating history with the Eurofighter, have a dummy spit because you didn't get all of the work share,,,Go it alone with what you have,,,The Rafale was a polished Mirage

Last edited:

British fighter jet makes emergency landing at Kagoshima airport

A British F-35 stealth fighter jet made an emergency landing Sunday at Kagoshima airport in southwestern Japan due to a malfunction, airport officials said.

A British F-35 stealth fighter jet made an emergency landing Sunday at Kagoshima airport in southwestern Japan due to a malfunction, airport officials said.

Yes.There are 1,200 of them flying, Are we really going to post every time there is a cockpit warning?

After Kerala India, Now British Tourist F-35 visits Japan for a month long Vacation....

I definitely think British are revenging US Tariffs imposed by Trump on Britain....

ALIS messing up again?

After Kerala India, Now British Tourist F-35 visits Japan for a month long Vacation....

I definitely think British are revenging US Tariffs imposed by Trump on Britain....

I did some research, and it appears you're completely wrong. I don't know if this is ignorance on your part, or a deliberate attempt to mislead us. Only you know.Current IAF F-35's are standard F-35A's. The only upgrade is being able to drop their nuke bomb and that's it. Israeli systems won't be upgraded for another year or two. Their EW upgrade is in POD form.

First, here's an article on the modifications made to the Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal (IsrAF) F-35Is Adir:

Modifications to the F-35I Adir: range and electronic warfare

(21 June 2025)

Why the Israeli Air Force is modifying its F-35I Adir aircraft: range, electronic warfare, integration of local weapons.

The Israeli Air Force has undertaken major modifications to its F-35I Adir, a derivative of the American F-35A. Officially authorized by the United States, this reengineering aims to meet specific tactical requirements, including extended range and the addition of electronic warfare (EW) modules adapted to regional threats. These adaptations enable them, for example, to carry out direct strikes in Iran without in-flight refueling or to integrate local weapons. This technical work is being carried out in a demanding operational context: neutralization of Iranian air defenses, nuclear targets, enemy electronic jamming, etc. It gives the Israeli fighter jet a real strategic advantage, reinforced by local maintenance capabilities [cf. the second article below concerning ALIS & ODIN].

This article offers a detailed analysis, divided into four parts, to examine the reasons behind these modifications, based on figures, concrete examples, and a desire to provide value to the reader.

The strategic reason for the modifications

The strategic reason for the modifications

Israel has secured a unique agreement with the United States to extensively modify its version of the F-35, known as the F-35I Adir, in order to meet strict operational requirements linked to its regional military doctrine. One of the main objectives is to ensure direct strike capability against Iran, located approximately 1,500 kilometers away, without the need for in-flight refueling. This autonomy reduces dependence on refueling aircraft, while limiting the risk of prolonged exposure to radar detection.

Another strategic imperative is to counter advanced ground-to-air systems deployed by Iran, such as the Russian-made S-300PMU-2. These defenses, equipped with long-range radars and high-performance missiles, require a high level of stealth and sophisticated electronic warfare capabilities. Israel has therefore obtained authorization to modify the original BAE AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare suite by integrating technologies developed locally by Elbit Systems. These sensors enable precise detection, targeted jamming, and electronic countermeasures adapted to the frequencies used in the region.

Finally, maintenance operations are centralized at the Nevatim air base, without going through Lockheed Martin’s logistics. This logistical autonomy ensures better aircraft availability while reducing downtime for heavy maintenance [cf. article below concerning ALIS & ODIN]. Although the hourly flight cost of the F-35 remains high—estimated at between €40,000 and €90,000—the ability to adapt and maintain the aircraft locally significantly enhances its operational effectiveness in a highly contested environment.

Technical modifications: autonomy and electronic warfare

Technical modifications: autonomy and electronic warfare

Israel has made substantial structural and electronic modifications to the F-35I Adir to enhance its autonomy and electronic warfare capabilities in heavily defended environments. These modifications are designed to maximize operational effectiveness over a wide range, with sensors adapted to regional threats.

Compliant external fuel tanks

One of the priorities was to extend autonomy without sacrificing stealth. To achieve this, Israel designed compliant external fuel tanks with low radar signature. Integrated into the fuselage and covered with absorbent materials, they do not significantly alter the aircraft’s radar profile. These tanks enable a range of over 2,200 km in cruise flight, making it possible to fly to Iran and back without refueling. They are attached using pylons designed specifically to preserve the jet’s aerodynamics and electromagnetic signature.Fighter jet rides

Modular platform and onboard computing

The F-35I’s Main Mission Computer (MMC) has been reconfigured to allow the integration of local modules in a plug-and-play architecture. This technical modularity allows the addition of Israeli software, sensors, data links, and targeting systems without recompiling all of the critical US systems. This choice aims to ensure the IDF’s functional independence in adapting the aircraft to future weapons or sensors as regional threats evolve, while maintaining the airframe’s stealth performance.

Next-generation electronic warfare

The original BAE Systems AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare system has been replaced or supplemented by a system developed by Elbit Systems. This device includes active jamming, digital decoys, and multi-spectral detection capabilities. It is designed to quickly detect and neutralize surveillance radars, infrared or electromagnetic guidance systems, and ground-to-air missile systems such as the Tor-M1 or S-300PMU-2. By providing autonomous EW coverage, the F-35I can engage in complex offensive missions without external support, even in areas saturated with enemy signals.

Integration of weapons and sensors

Integration of weapons and sensors

One of the key elements of the F-35I Adir program is the ability for Tsahal to integrate its own equipment into a platform normally locked down by the American manufacturer Lockheed Martin. Thanks to adaptations to the Main Mission Computer, Israel can insert locally developed weapons and sensors directly into the aircraft’s digital environment, while maintaining compatibility with the original mission software. This greatly enhances the aircraft’s tactical flexibility in the regional context.

Local weapons

Israel designed the F-35I to carry air-to-air missiles and domestically manufactured guided bombs in its internal bays while maintaining its low radar signature. Although the exact list of these weapons remains confidential, tests have been conducted since 2020 with local munitions. It is highly likely that missiles such as the Python-5 or Derby radar-guided missiles will be integrated, alongside SPICE-1000 or SPICE-2000 guided bombs, capable of striking targets with meter-level accuracy at ranges of over 100 kilometers. Integration into the fuselage avoids increasing drag or radar signature, which would be the case with external pylons.

Additional sensors

Israel also plans to add optical and electro-optical pods, such as the Rafael Litening 5, for more specific air-to-ground missions than those permitted by the original US EOTS (Electro-Optical Targeting System). The Litening 5 offers more accurate detection of moving targets and identification capabilities better suited to operations in complex environments such as urban or semi-mountainous areas.

Data link system

Finally, the Israeli datalink, developed for the F-35I, bypasses the MADL (Multifunction Advanced Datalink) data link imposed by the United States. This local system allows the F-35I to communicate in real time with other Israeli aircraft (F-15I Ra’am, F-16I Sufa), ground control systems, MALE drones, and missile defense batteries such as David’s Sling. This cross-platform compatibility enhances the F-35I’s integration into the Israeli Air Force’s network-centric operations, ensuring tactical data transmission without US format constraints.

Operational results and challenges

Operational results and challenges

Feedback from the field

The modifications made to the F-35I Adir have not remained theoretical. They have been tested repeatedly in real combat situations. Since 2021, the aircraft have participated in the interception of Iranian drones approaching Israeli borders, demonstrating their long-range detection and interception capabilities. In 2023, the F-35Is were used in missions to neutralize ballistic missiles in flight, including missiles launched from southern Lebanon and Syria targeting northern Israeli territory.Fighter jet rides

The most significant operations took place between 2024 and 2025, with deep strikes on sensitive infrastructure in Iran. These raids, carried out at very long range, involved penetrating areas monitored by S-300PMU-2 radars and protected by medium-range surface-to-air batteries. The F-35I proved its ability to pass through these defenses, engage targets, and then leave without being detected. The IDF claims that more than 100 military targets were neutralized, including nuclear research sites and drone and missile warehouses.

Costs and availability

The operational cost of the F-35I remains high, with estimates ranging from €40,000 to €41,000 per flight hour. This cost includes fuel consumption, maintenance, spare parts, and technical personnel costs. However, Israel’s decision to carry out all maintenance at the Nevatim base reduces response times, increases aircraft availability and limits dependence on the US manufacturer for heavy logistics. This independence comes at a price, but it ensures a level of tactical responsiveness that is difficult to achieve in other armies equipped with the F-35.

Limitations

Limitations

The main limitation of the fleet at present is its small size. Of the 50 aircraft ordered, only 36 to 39 will be operational in 2025. The rest are still being delivered or modified. This number limits Israel’s ability to conduct saturation operations or engage on multiple fronts simultaneously. In addition, the development of passive detection technologies (long-range IRST sensors, low-wave radar networks) by Iran and its allies could, in the medium term, reduce the stealth advantage of the F-35I [and all F-35s; not specificly IsrAF ones]. Finally, maintaining the high technological level of these aircraft requires rigorous budgetary monitoring and a solid industrial capacity to integrate future software and hardware upgrades without depending on the US schedule.

These modifications make the F-35I Adir unique. The addition of external fuel tanks, the Elbit electronic warfare platform, the local datalink, and the integration of Israeli weapons make this fighter jet a holistic system, tailored for strikes in highly defended areas of Iran. These adaptations enable long, autonomous, stealthy flights that are perfectly connected to the Israeli military infrastructure. By combining an advanced tactical approach with cutting-edge aeronautical engineering, the F-35 Adir is positioned as a decisive strategic tool. However, budgetary and industrial challenges, as well as the evolution of enemy defenses, now require constant vigilance to maintain its effectiveness. /end

Is it enough? No, it isn't: fact is that the Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal (IsrAF) does not use ALIS, nor will it use ODIN, what you were careful not to mention. Modesty, no doubt.

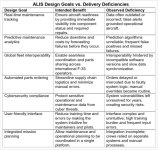

Coffee Break: Armed Madhouse – The Trouble with ALIS

(12.08.2025)

The F-35 fighter jet is the most expensive weapons program in U.S. history, but one of its biggest failures isn’t in the air — it’s on the ground. The Pentagon’s Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), conceived as an ambitious plan to revolutionize fighter jet maintenance and logistics, collapsed under the weight of bad design, poor coordination, and perverse incentives that reward failure as readily as success. Its troubled successor, the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), has stumbled out of the gate, revealing a deeper, recurring syndrome in U.S. government technology programs — a systemic incapacity to deliver on large-scale, high-cost projects, where failure is not just common but structurally baked into the process. This article uses the rise and fall of ALIS, and ODIN’s faltering replacement effort, to illustrate how that syndrome operates and why it persists.

ALIS’s collapse was not the result of a single flaw but of compounding failures that undermined it from conception to deployment. Conceived as the digital nervous system of the F-35 program, ALIS was meant to track parts and maintenance in real time, streamline repairs, predict failures before they happened, and connect a global fleet with seamless efficiency. In reality, it became a sprawling, brittle, and chronically unreliable burden. Software updates routinely broke existing functions, maintenance crews spent as much time troubleshooting the system as servicing the aircraft, and pilots were grounded not by enemy action but by bad data and system errors. What was billed as a force multiplier instead became an expensive liability — a case study in how poor architecture, weak oversight, and skewed incentives can cripple even the most critical capabilities.

Israel Says No to ALIS

Perhaps the most telling indictment of ALIS came not from a congressional hearing or a Pentagon audit, but from the operational choices of one of America’s closest military partners. In 2016, when Israel received its first F-35I “Adir” fighters, it declined to connect them to the global ALIS network at all. Instead, the Israeli Air Force built its own independent logistics, maintenance, and mission systems to support the jets. Officially, this decision was framed as a matter of sovereignty and cybersecurity — Israel wanted to ensure that no foreign entity could monitor or interfere with its aircraft operations. Unofficially, it was also an acknowledgment that ALIS, as delivered, could not be relied upon for timely, accurate, or secure sustainment.

For a program whose central selling point was a globally integrated logistics backbone, one of its earliest foreign customers effectively voted “no confidence” and walked away, creating a precedent that other partners quietly noted. The Pentagon’s answer to such mounting dissatisfaction was ODIN — a fresh start in name, but as events would quickly show, a system fated to inherit many of the same flaws that doomed ALIS.

ODIN: The Replacement That Stumbled

In 2020, the Pentagon announced that ALIS would be phased out and replaced by the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), a “modern, cloud-native” system promising faster updates, stronger cybersecurity, and a leaner, modular design. But almost immediately, ODIN began exhibiting the same flaws it was meant to fix. Hardware shortages delayed initial deployment, integration with legacy F-35 data pipelines proved more complex than anticipated, and shifting requirements coupled with uncertain funding caused repeated schedule slips. Most tellingly, ODIN’s reliance on a patchwork of government, Lockheed Martin, and subcontractor teams recreated the fractured accountability that had hobbled ALIS from the start.

By 2023, the Department of Defense quietly acknowledged that ODIN would not fully replace ALIS for years, and in some cases, the two systems would operate in parallel indefinitely. This hybrid setup perpetuated the very inefficiencies ODIN was supposed to eliminate — maintainers still had to wrestle with multiple interfaces, inconsistent data, and duplicated workflows. In effect, ODIN became less a clean replacement than an ongoing patchwork, weighed down by inherited design flaws, bureaucratic inertia, and the same perverse incentives that rewarded visible activity over actual capability.

The Consequences of Failure

Despite roughly $1 billion spent on ALIS and hundreds of millions more on ODIN, the F-35 fleet’s mission-capable rate remains stuck at about 55%, far below the 85–90% target. ALIS’s failures—and ODIN’s slow rollout—have contributed to chronic maintenance delays, inflated sustainment costs, and reduced operational availability, undermining the F-35’s ability to meet its core mission requirements.

From ALIS to the Bigger Problem: Government Project Sandbagging

The ALIS debacle — and ODIN’s halting attempt at redemption — is not an isolated failure but part of a recurring pathology in large U.S. government technology programs. This broader failure syndrome, which can be called project sandbagging, thrives in environments where perverse incentives reward slow progress, extended timelines, and budget inflation over timely, effective delivery. In such programs, failure rarely harms the contractors or agencies involved; instead, it becomes a pretext for additional funding, prolonged contracts, and diluted accountability. The very complexity that justifies massive budgets also shields programs from scrutiny, allowing delays and underperformance to be reframed as the inevitable costs of “managing risk” in ambitious projects. Too often, progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations rather than delivered capability. ALIS is simply a particularly vivid example of how sandbagging erodes readiness, wastes resources, and normalizes failure — a fate shared by other major Defense Department technology projects.

When the Sandbags Are Removed: SpaceX vs. NASA

The gap between SpaceX and NASA’s congressionally directed SLS/Orion/EGS program is a rare natural experiment in incentives. Under fixed-price, milestone-based Space Act Agreements, SpaceX fielded Falcon 9/Heavy and Crew Dragon and built multiple Starship prototypes on rapid cycles; NASA, by contrast, has spent over $55 billion on SLS, Orion, and ground systems through the planned Artemis II date, with per-launch production/operations estimated at about $4.1 billion—a cadence and cost structure widely flagged as unsustainable.

SpaceX’s COTS/CRS/Commercial Crew work tied payments to verified, operational outcomes (e.g., ISS cargo and crew delivery), with NASA’s own OIG estimating ~$55 M per Dragon seat versus ~$90 M for Starliner. In contrast, Congress required NASA to build SLS with Shuttle/Constellation heritage and legacy contracts — locking in cost-plus dynamics, fragmented accountability, and low competitive pressure. While SLS is designed for deep-space crewed missions and thus faces higher safety margins, its cost and schedule gulf with SpaceX still reflects a stark disparity in structural incentives: one path rewards delivery and efficiency, the other sustains delay and budget growth under the banner of “managing risk.” That disparity is the essence of project sandbagging — a system where progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations, not delivered capability.

Conclusion

The failure of ALIS is not a rare mishap — it is a case study in a chronic U.S. government failure mode. It reflects a recurring pattern: fragmented accountability, contractor dominance, risk-averse governance, and illusory milestone-driven progress that substitutes process for performance. Like many federal IT programs, it was built under cost-plus contracts, insulated from disruptive innovation, and allowed to persist despite user distrust and operational dysfunction.

The slow, incomplete transition to ODIN has not resolved these flaws — it has entrenched them. ALIS’s legacy is more than the logistical hobbling of the F-35 program; it is a warning that without structural reform in procurement, oversight, and incentives, critical technology projects will continue to sandbag transformation while consuming vast public resources. If future programs — including those now on the drawing board — are to avoid the same fate, the cost of inaction must be understood as measured not just in dollars, but in lost capability.

Curbing the entrenched practice of project sandbagging will require reforms that change both the incentives and the accountability structures that sustain it. The following measures address the pattern of incentive and oversight failures that doomed ALIS and now hinder ODIN:

- Tie contractor profit to operational outcomes, not just deliverables.

Move away from cost-plus contracts toward milestone payments linked to verified, in-service performance. This makes profit contingent on the system actually working as promised. - Enforce independent technical audits at multiple project stages.

Mandate third-party verification of progress, functionality, and readiness before approving further funding. Auditors should report directly to Congress or another oversight body, bypassing the program office’s chain of command. - Adopt modular, open-architecture requirements.

Design programs so that components can be upgraded or replaced independently. This reduces lock-in to flawed subsystems and encourages competitive sourcing. - Institute “sunset clauses” for underperforming programs.

Set predefined thresholds for cost, schedule, and readiness; if breached, the program must be re-competed, restructured, or terminated. This makes failure a risk for the implementers, not just the warfighters. /end

By shifting incentives toward timely, functional delivery, these measures would make it harder for stakeholders to profit from delay and under-performance. The F-35’s ALIS and ODIN experience demonstrates what results when such guardrails are absent: costly, drawn-out efforts that erode readiness while delivering far less than promised. That is the central lesson of ALIS and ODIN, and why systemic reform is mission-critical. Until the sandbags are removed, the United States will keep mistaking motion for progress — and paying a premium for failure.

Finally, and to conclude, I recall the words of the former Pakistani ambassador in Washington about the employment restrictions imposed by the Americans to military aircrafts (weapons) [The Diplomat], to which Israelis are not subject.

All of this is very, very far from your claim.

Amarante

In short.I did some research, and it appears you're completely wrong. I don't know if this is ignorance on your part, or a deliberate attempt to mislead us. Only you know.

First, here's an article on the modifications made to the Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal (IsrAF) F-35Is Adir:

Modifications to the F-35I Adir: range and electronic warfare

(21 June 2025)

Why the Israeli Air Force is modifying its F-35I Adir aircraft: range, electronic warfare, integration of local weapons.The Israeli Air Force has undertaken major modifications to its F-35I Adir, a derivative of the American F-35A. Officially authorized by the United States, this reengineering aims to meet specific tactical requirements, including extended range and the addition of electronic warfare (EW) modules adapted to regional threats. These adaptations enable them, for example, to carry out direct strikes in Iran without in-flight refueling or to integrate local weapons. This technical work is being carried out in a demanding operational context: neutralization of Iranian air defenses, nuclear targets, enemy electronic jamming, etc. It gives the Israeli fighter jet a real strategic advantage, reinforced by local maintenance capabilities [cf. the second article below concerning ALIS & ODIN].This article offers a detailed analysis, divided into four parts, to examine the reasons behind these modifications, based on figures, concrete examples, and a desire to provide value to the reader.

The strategic reason for the modificationsIsrael has secured a unique agreement with the United States to extensively modify its version of the F-35, known as the F-35I Adir, in order to meet strict operational requirements linked to its regional military doctrine. One of the main objectives is to ensure direct strike capability against Iran, located approximately 1,500 kilometers away, without the need for in-flight refueling. This autonomy reduces dependence on refueling aircraft, while limiting the risk of prolonged exposure to radar detection.Another strategic imperative is to counter advanced ground-to-air systems deployed by Iran, such as the Russian-made S-300PMU-2. These defenses, equipped with long-range radars and high-performance missiles, require a high level of stealth and sophisticated electronic warfare capabilities. Israel has therefore obtained authorization to modify the original BAE AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare suite by integrating technologies developed locally by Elbit Systems. These sensors enable precise detection, targeted jamming, and electronic countermeasures adapted to the frequencies used in the region.Finally, maintenance operations are centralized at the Nevatim air base, without going through Lockheed Martin’s logistics. This logistical autonomy ensures better aircraft availability while reducing downtime for heavy maintenance [cf. article below concerning ALIS & ODIN]. Although the hourly flight cost of the F-35 remains high—estimated at between €40,000 and €90,000—the ability to adapt and maintain the aircraft locally significantly enhances its operational effectiveness in a highly contested environment.

Technical modifications: autonomy and electronic warfareIsrael has made substantial structural and electronic modifications to the F-35I Adir to enhance its autonomy and electronic warfare capabilities in heavily defended environments. These modifications are designed to maximize operational effectiveness over a wide range, with sensors adapted to regional threats.Compliant external fuel tanksOne of the priorities was to extend autonomy without sacrificing stealth. To achieve this, Israel designed compliant external fuel tanks with low radar signature. Integrated into the fuselage and covered with absorbent materials, they do not significantly alter the aircraft’s radar profile. These tanks enable a range of over 2,200 km in cruise flight, making it possible to fly to Iran and back without refueling. They are attached using pylons designed specifically to preserve the jet’s aerodynamics and electromagnetic signature.Fighter jet ridesModular platform and onboard computingThe F-35I’s Main Mission Computer (MMC) has been reconfigured to allow the integration of local modules in a plug-and-play architecture. This technical modularity allows the addition of Israeli software, sensors, data links, and targeting systems without recompiling all of the critical US systems. This choice aims to ensure the IDF’s functional independence in adapting the aircraft to future weapons or sensors as regional threats evolve, while maintaining the airframe’s stealth performance.Next-generation electronic warfareThe original BAE Systems AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare system has been replaced or supplemented by a system developed by Elbit Systems. This device includes active jamming, digital decoys, and multi-spectral detection capabilities. It is designed to quickly detect and neutralize surveillance radars, infrared or electromagnetic guidance systems, and ground-to-air missile systems such as the Tor-M1 or S-300PMU-2. By providing autonomous EW coverage, the F-35I can engage in complex offensive missions without external support, even in areas saturated with enemy signals.

Integration of weapons and sensorsOne of the key elements of the F-35I Adir program is the ability for Tsahal to integrate its own equipment into a platform normally locked down by the American manufacturer Lockheed Martin. Thanks to adaptations to the Main Mission Computer, Israel can insert locally developed weapons and sensors directly into the aircraft’s digital environment, while maintaining compatibility with the original mission software. This greatly enhances the aircraft’s tactical flexibility in the regional context.Local weaponsIsrael designed the F-35I to carry air-to-air missiles and domestically manufactured guided bombs in its internal bays while maintaining its low radar signature. Although the exact list of these weapons remains confidential, tests have been conducted since 2020 with local munitions. It is highly likely that missiles such as the Python-5 or Derby radar-guided missiles will be integrated, alongside SPICE-1000 or SPICE-2000 guided bombs, capable of striking targets with meter-level accuracy at ranges of over 100 kilometers. Integration into the fuselage avoids increasing drag or radar signature, which would be the case with external pylons.Additional sensorsIsrael also plans to add optical and electro-optical pods, such as the Rafael Litening 5, for more specific air-to-ground missions than those permitted by the original US EOTS (Electro-Optical Targeting System). The Litening 5 offers more accurate detection of moving targets and identification capabilities better suited to operations in complex environments such as urban or semi-mountainous areas.Data link systemFinally, the Israeli datalink, developed for the F-35I, bypasses the MADL (Multifunction Advanced Datalink) data link imposed by the United States. This local system allows the F-35I to communicate in real time with other Israeli aircraft (F-15I Ra’am, F-16I Sufa), ground control systems, MALE drones, and missile defense batteries such as David’s Sling. This cross-platform compatibility enhances the F-35I’s integration into the Israeli Air Force’s network-centric operations, ensuring tactical data transmission without US format constraints.

Operational results and challengesFeedback from the fieldThe modifications made to the F-35I Adir have not remained theoretical. They have been tested repeatedly in real combat situations. Since 2021, the aircraft have participated in the interception of Iranian drones approaching Israeli borders, demonstrating their long-range detection and interception capabilities. In 2023, the F-35Is were used in missions to neutralize ballistic missiles in flight, including missiles launched from southern Lebanon and Syria targeting northern Israeli territory.Fighter jet ridesThe most significant operations took place between 2024 and 2025, with deep strikes on sensitive infrastructure in Iran. These raids, carried out at very long range, involved penetrating areas monitored by S-300PMU-2 radars and protected by medium-range surface-to-air batteries. The F-35I proved its ability to pass through these defenses, engage targets, and then leave without being detected. The IDF claims that more than 100 military targets were neutralized, including nuclear research sites and drone and missile warehouses.Costs and availabilityThe operational cost of the F-35I remains high, with estimates ranging from €40,000 to €41,000 per flight hour. This cost includes fuel consumption, maintenance, spare parts, and technical personnel costs. However, Israel’s decision to carry out all maintenance at the Nevatim base reduces response times, increases aircraft availability and limits dependence on the US manufacturer for heavy logistics. This independence comes at a price, but it ensures a level of tactical responsiveness that is difficult to achieve in other armies equipped with the F-35.

LimitationsThe main limitation of the fleet at present is its small size. Of the 50 aircraft ordered, only 36 to 39 will be operational in 2025. The rest are still being delivered or modified. This number limits Israel’s ability to conduct saturation operations or engage on multiple fronts simultaneously. In addition, the development of passive detection technologies (long-range IRST sensors, low-wave radar networks) by Iran and its allies could, in the medium term, reduce the stealth advantage of the F-35I [and all F-35s; not specificly IsrAF ones]. Finally, maintaining the high technological level of these aircraft requires rigorous budgetary monitoring and a solid industrial capacity to integrate future software and hardware upgrades without depending on the US schedule.These modifications make the F-35I Adir unique. The addition of external fuel tanks, the Elbit electronic warfare platform, the local datalink, and the integration of Israeli weapons make this fighter jet a holistic system, tailored for strikes in highly defended areas of Iran. These adaptations enable long, autonomous, stealthy flights that are perfectly connected to the Israeli military infrastructure. By combining an advanced tactical approach with cutting-edge aeronautical engineering, the F-35 Adir is positioned as a decisive strategic tool. However, budgetary and industrial challenges, as well as the evolution of enemy defenses, now require constant vigilance to maintain its effectiveness. /end

Is it enough? No, it isn't: fact is that the Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal (IsrAF) does not use ALIS, nor will it use ODIN, what you were careful not to mention. Modesty, no doubt.

Coffee Break: Armed Madhouse – The Trouble with ALIS

(12.08.2025)

The F-35 fighter jet is the most expensive weapons program in U.S. history, but one of its biggest failures isn’t in the air — it’s on the ground. The Pentagon’s Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), conceived as an ambitious plan to revolutionize fighter jet maintenance and logistics, collapsed under the weight of bad design, poor coordination, and perverse incentives that reward failure as readily as success. Its troubled successor, the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), has stumbled out of the gate, revealing a deeper, recurring syndrome in U.S. government technology programs — a systemic incapacity to deliver on large-scale, high-cost projects, where failure is not just common but structurally baked into the process. This article uses the rise and fall of ALIS, and ODIN’s faltering replacement effort, to illustrate how that syndrome operates and why it persists.ALIS’s collapse was not the result of a single flaw but of compounding failures that undermined it from conception to deployment. Conceived as the digital nervous system of the F-35 program, ALIS was meant to track parts and maintenance in real time, streamline repairs, predict failures before they happened, and connect a global fleet with seamless efficiency. In reality, it became a sprawling, brittle, and chronically unreliable burden. Software updates routinely broke existing functions, maintenance crews spent as much time troubleshooting the system as servicing the aircraft, and pilots were grounded not by enemy action but by bad data and system errors. What was billed as a force multiplier instead became an expensive liability — a case study in how poor architecture, weak oversight, and skewed incentives can cripple even the most critical capabilities.Israel Says No to ALISPerhaps the most telling indictment of ALIS came not from a congressional hearing or a Pentagon audit, but from the operational choices of one of America’s closest military partners. In 2016, when Israel received its first F-35I “Adir” fighters, it declined to connect them to the global ALIS network at all. Instead, the Israeli Air Force built its own independent logistics, maintenance, and mission systems to support the jets. Officially, this decision was framed as a matter of sovereignty and cybersecurity — Israel wanted to ensure that no foreign entity could monitor or interfere with its aircraft operations. Unofficially, it was also an acknowledgment that ALIS, as delivered, could not be relied upon for timely, accurate, or secure sustainment.For a program whose central selling point was a globally integrated logistics backbone, one of its earliest foreign customers effectively voted “no confidence” and walked away, creating a precedent that other partners quietly noted. The Pentagon’s answer to such mounting dissatisfaction was ODIN — a fresh start in name, but as events would quickly show, a system fated to inherit many of the same flaws that doomed ALIS.ODIN: The Replacement That StumbledIn 2020, the Pentagon announced that ALIS would be phased out and replaced by the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), a “modern, cloud-native” system promising faster updates, stronger cybersecurity, and a leaner, modular design. But almost immediately, ODIN began exhibiting the same flaws it was meant to fix. Hardware shortages delayed initial deployment, integration with legacy F-35 data pipelines proved more complex than anticipated, and shifting requirements coupled with uncertain funding caused repeated schedule slips. Most tellingly, ODIN’s reliance on a patchwork of government, Lockheed Martin, and subcontractor teams recreated the fractured accountability that had hobbled ALIS from the start.By 2023, the Department of Defense quietly acknowledged that ODIN would not fully replace ALIS for years, and in some cases, the two systems would operate in parallel indefinitely. This hybrid setup perpetuated the very inefficiencies ODIN was supposed to eliminate — maintainers still had to wrestle with multiple interfaces, inconsistent data, and duplicated workflows. In effect, ODIN became less a clean replacement than an ongoing patchwork, weighed down by inherited design flaws, bureaucratic inertia, and the same perverse incentives that rewarded visible activity over actual capability.The Consequences of FailureDespite roughly $1 billion spent on ALIS and hundreds of millions more on ODIN, the F-35 fleet’s mission-capable rate remains stuck at about 55%, far below the 85–90% target. ALIS’s failures—and ODIN’s slow rollout—have contributed to chronic maintenance delays, inflated sustainment costs, and reduced operational availability, undermining the F-35’s ability to meet its core mission requirements.From ALIS to the Bigger Problem: Government Project SandbaggingThe ALIS debacle — and ODIN’s halting attempt at redemption — is not an isolated failure but part of a recurring pathology in large U.S. government technology programs. This broader failure syndrome, which can be called project sandbagging, thrives in environments where perverse incentives reward slow progress, extended timelines, and budget inflation over timely, effective delivery. In such programs, failure rarely harms the contractors or agencies involved; instead, it becomes a pretext for additional funding, prolonged contracts, and diluted accountability. The very complexity that justifies massive budgets also shields programs from scrutiny, allowing delays and underperformance to be reframed as the inevitable costs of “managing risk” in ambitious projects. Too often, progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations rather than delivered capability. ALIS is simply a particularly vivid example of how sandbagging erodes readiness, wastes resources, and normalizes failure — a fate shared by other major Defense Department technology projects.When the Sandbags Are Removed: SpaceX vs. NASA The gap between SpaceX and NASA’s congressionally directed SLS/Orion/EGS program is a rare natural experiment in incentives. Under fixed-price, milestone-based Space Act Agreements, SpaceX fielded Falcon 9/Heavy and Crew Dragon and built multiple Starship prototypes on rapid cycles; NASA, by contrast, has spent over $55 billion on SLS, Orion, and ground systems through the planned Artemis II date, with per-launch production/operations estimated at about $4.1 billion—a cadence and cost structure widely flagged as unsustainable.SpaceX’s COTS/CRS/Commercial Crew work tied payments to verified, operational outcomes (e.g., ISS cargo and crew delivery), with NASA’s own OIG estimating ~$55 M per Dragon seat versus ~$90 M for Starliner. In contrast, Congress required NASA to build SLS with Shuttle/Constellation heritage and legacy contracts — locking in cost-plus dynamics, fragmented accountability, and low competitive pressure. While SLS is designed for deep-space crewed missions and thus faces higher safety margins, its cost and schedule gulf with SpaceX still reflects a stark disparity in structural incentives: one path rewards delivery and efficiency, the other sustains delay and budget growth under the banner of “managing risk.” That disparity is the essence of project sandbagging — a system where progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations, not delivered capability.ConclusionThe failure of ALIS is not a rare mishap — it is a case study in a chronic U.S. government failure mode. It reflects a recurring pattern: fragmented accountability, contractor dominance, risk-averse governance, and illusory milestone-driven progress that substitutes process for performance. Like many federal IT programs, it was built under cost-plus contracts, insulated from disruptive innovation, and allowed to persist despite user distrust and operational dysfunction.The slow, incomplete transition to ODIN has not resolved these flaws — it has entrenched them. ALIS’s legacy is more than the logistical hobbling of the F-35 program; it is a warning that without structural reform in procurement, oversight, and incentives, critical technology projects will continue to sandbag transformation while consuming vast public resources. If future programs — including those now on the drawing board — are to avoid the same fate, the cost of inaction must be understood as measured not just in dollars, but in lost capability.Curbing the entrenched practice of project sandbagging will require reforms that change both the incentives and the accountability structures that sustain it. The following measures address the pattern of incentive and oversight failures that doomed ALIS and now hinder ODIN:

- Tie contractor profit to operational outcomes, not just deliverables.

Move away from cost-plus contracts toward milestone payments linked to verified, in-service performance. This makes profit contingent on the system actually working as promised.- Enforce independent technical audits at multiple project stages.

Mandate third-party verification of progress, functionality, and readiness before approving further funding. Auditors should report directly to Congress or another oversight body, bypassing the program office’s chain of command.- Adopt modular, open-architecture requirements.

Design programs so that components can be upgraded or replaced independently. This reduces lock-in to flawed subsystems and encourages competitive sourcing.- Institute “sunset clauses” for underperforming programs.

Set predefined thresholds for cost, schedule, and readiness; if breached, the program must be re-competed, restructured, or terminated. This makes failure a risk for the implementers, not just the warfighters. /endBy shifting incentives toward timely, functional delivery, these measures would make it harder for stakeholders to profit from delay and under-performance. The F-35’s ALIS and ODIN experience demonstrates what results when such guardrails are absent: costly, drawn-out efforts that erode readiness while delivering far less than promised. That is the central lesson of ALIS and ODIN, and why systemic reform is mission-critical. Until the sandbags are removed, the United States will keep mistaking motion for progress — and paying a premium for failure.

Finally, and to conclude, I recall the words of the former Pakistani ambassador in Washington about the employment restrictions imposed by the Americans to military aircrafts (weapons) [The Diplomat], to which Israelis are not subject.

All of this is very, very far from your claim.

Amarante

additional fuel tanks.

( Not really a change, more of a addition).

Changes in software to use israeli weapons, and israeli data links to communicate and work along with other israeli assests.

And changes in EW, which will make sense as israel will extensively use f35, could include using the EW suite in full spectrum "war mode", if the EW in israeli f35 is same as EW in USAF f35, that does pose a potential exposer risk for US.

And israeli hub, for general maintenence.

It’s not bas but it’s partial. For exemple:In short.

additional fuel tanks.

( Not really a change, more of a addition).

Changes in software to use israeli weapons, and israeli data links to communicate and work along with other israeli assests.

And changes in EW, which will make sense as israel will extensively use f35, could include using the EW suite in full spectrum "war mode", if the EW in israeli f35 is same as EW in USAF f35, that does pose a potential exposer risk for US.

And israeli hub, for general maintenence.

Impressive. Did you write this blogpost ?I did some research, and it appears you're completely wrong. I don't know if this is ignorance on your part, or a deliberate attempt to mislead us. Only you know.

First, here's an article on the modifications made to the Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal (IsrAF) F-35Is Adir:

Modifications to the F-35I Adir: range and electronic warfare

(21 June 2025)

Why the Israeli Air Force is modifying its F-35I Adir aircraft: range, electronic warfare, integration of local weapons.The Israeli Air Force has undertaken major modifications to its F-35I Adir, a derivative of the American F-35A. Officially authorized by the United States, this reengineering aims to meet specific tactical requirements, including extended range and the addition of electronic warfare (EW) modules adapted to regional threats. These adaptations enable them, for example, to carry out direct strikes in Iran without in-flight refueling or to integrate local weapons. This technical work is being carried out in a demanding operational context: neutralization of Iranian air defenses, nuclear targets, enemy electronic jamming, etc. It gives the Israeli fighter jet a real strategic advantage, reinforced by local maintenance capabilities [cf. the second article below concerning ALIS & ODIN].This article offers a detailed analysis, divided into four parts, to examine the reasons behind these modifications, based on figures, concrete examples, and a desire to provide value to the reader.

The strategic reason for the modificationsIsrael has secured a unique agreement with the United States to extensively modify its version of the F-35, known as the F-35I Adir, in order to meet strict operational requirements linked to its regional military doctrine. One of the main objectives is to ensure direct strike capability against Iran, located approximately 1,500 kilometers away, without the need for in-flight refueling. This autonomy reduces dependence on refueling aircraft, while limiting the risk of prolonged exposure to radar detection.Another strategic imperative is to counter advanced ground-to-air systems deployed by Iran, such as the Russian-made S-300PMU-2. These defenses, equipped with long-range radars and high-performance missiles, require a high level of stealth and sophisticated electronic warfare capabilities. Israel has therefore obtained authorization to modify the original BAE AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare suite by integrating technologies developed locally by Elbit Systems. These sensors enable precise detection, targeted jamming, and electronic countermeasures adapted to the frequencies used in the region.Finally, maintenance operations are centralized at the Nevatim air base, without going through Lockheed Martin’s logistics. This logistical autonomy ensures better aircraft availability while reducing downtime for heavy maintenance [cf. article below concerning ALIS & ODIN]. Although the hourly flight cost of the F-35 remains high—estimated at between €40,000 and €90,000—the ability to adapt and maintain the aircraft locally significantly enhances its operational effectiveness in a highly contested environment.

Technical modifications: autonomy and electronic warfareIsrael has made substantial structural and electronic modifications to the F-35I Adir to enhance its autonomy and electronic warfare capabilities in heavily defended environments. These modifications are designed to maximize operational effectiveness over a wide range, with sensors adapted to regional threats.Compliant external fuel tanksOne of the priorities was to extend autonomy without sacrificing stealth. To achieve this, Israel designed compliant external fuel tanks with low radar signature. Integrated into the fuselage and covered with absorbent materials, they do not significantly alter the aircraft’s radar profile. These tanks enable a range of over 2,200 km in cruise flight, making it possible to fly to Iran and back without refueling. They are attached using pylons designed specifically to preserve the jet’s aerodynamics and electromagnetic signature.Fighter jet ridesModular platform and onboard computingThe F-35I’s Main Mission Computer (MMC) has been reconfigured to allow the integration of local modules in a plug-and-play architecture. This technical modularity allows the addition of Israeli software, sensors, data links, and targeting systems without recompiling all of the critical US systems. This choice aims to ensure the IDF’s functional independence in adapting the aircraft to future weapons or sensors as regional threats evolve, while maintaining the airframe’s stealth performance.Next-generation electronic warfareThe original BAE Systems AN/ASQ-239 electronic warfare system has been replaced or supplemented by a system developed by Elbit Systems. This device includes active jamming, digital decoys, and multi-spectral detection capabilities. It is designed to quickly detect and neutralize surveillance radars, infrared or electromagnetic guidance systems, and ground-to-air missile systems such as the Tor-M1 or S-300PMU-2. By providing autonomous EW coverage, the F-35I can engage in complex offensive missions without external support, even in areas saturated with enemy signals.

Integration of weapons and sensorsOne of the key elements of the F-35I Adir program is the ability for Tsahal to integrate its own equipment into a platform normally locked down by the American manufacturer Lockheed Martin. Thanks to adaptations to the Main Mission Computer, Israel can insert locally developed weapons and sensors directly into the aircraft’s digital environment, while maintaining compatibility with the original mission software. This greatly enhances the aircraft’s tactical flexibility in the regional context.Local weaponsIsrael designed the F-35I to carry air-to-air missiles and domestically manufactured guided bombs in its internal bays while maintaining its low radar signature. Although the exact list of these weapons remains confidential, tests have been conducted since 2020 with local munitions. It is highly likely that missiles such as the Python-5 or Derby radar-guided missiles will be integrated, alongside SPICE-1000 or SPICE-2000 guided bombs, capable of striking targets with meter-level accuracy at ranges of over 100 kilometers. Integration into the fuselage avoids increasing drag or radar signature, which would be the case with external pylons.Additional sensorsIsrael also plans to add optical and electro-optical pods, such as the Rafael Litening 5, for more specific air-to-ground missions than those permitted by the original US EOTS (Electro-Optical Targeting System). The Litening 5 offers more accurate detection of moving targets and identification capabilities better suited to operations in complex environments such as urban or semi-mountainous areas.Data link systemFinally, the Israeli datalink, developed for the F-35I, bypasses the MADL (Multifunction Advanced Datalink) data link imposed by the United States. This local system allows the F-35I to communicate in real time with other Israeli aircraft (F-15I Ra’am, F-16I Sufa), ground control systems, MALE drones, and missile defense batteries such as David’s Sling. This cross-platform compatibility enhances the F-35I’s integration into the Israeli Air Force’s network-centric operations, ensuring tactical data transmission without US format constraints.

Operational results and challengesFeedback from the fieldThe modifications made to the F-35I Adir have not remained theoretical. They have been tested repeatedly in real combat situations. Since 2021, the aircraft have participated in the interception of Iranian drones approaching Israeli borders, demonstrating their long-range detection and interception capabilities. In 2023, the F-35Is were used in missions to neutralize ballistic missiles in flight, including missiles launched from southern Lebanon and Syria targeting northern Israeli territory.Fighter jet ridesThe most significant operations took place between 2024 and 2025, with deep strikes on sensitive infrastructure in Iran. These raids, carried out at very long range, involved penetrating areas monitored by S-300PMU-2 radars and protected by medium-range surface-to-air batteries. The F-35I proved its ability to pass through these defenses, engage targets, and then leave without being detected. The IDF claims that more than 100 military targets were neutralized, including nuclear research sites and drone and missile warehouses.Costs and availabilityThe operational cost of the F-35I remains high, with estimates ranging from €40,000 to €41,000 per flight hour. This cost includes fuel consumption, maintenance, spare parts, and technical personnel costs. However, Israel’s decision to carry out all maintenance at the Nevatim base reduces response times, increases aircraft availability and limits dependence on the US manufacturer for heavy logistics. This independence comes at a price, but it ensures a level of tactical responsiveness that is difficult to achieve in other armies equipped with the F-35.

LimitationsThe main limitation of the fleet at present is its small size. Of the 50 aircraft ordered, only 36 to 39 will be operational in 2025. The rest are still being delivered or modified. This number limits Israel’s ability to conduct saturation operations or engage on multiple fronts simultaneously. In addition, the development of passive detection technologies (long-range IRST sensors, low-wave radar networks) by Iran and its allies could, in the medium term, reduce the stealth advantage of the F-35I [and all F-35s; not specificly IsrAF ones]. Finally, maintaining the high technological level of these aircraft requires rigorous budgetary monitoring and a solid industrial capacity to integrate future software and hardware upgrades without depending on the US schedule.These modifications make the F-35I Adir unique. The addition of external fuel tanks, the Elbit electronic warfare platform, the local datalink, and the integration of Israeli weapons make this fighter jet a holistic system, tailored for strikes in highly defended areas of Iran. These adaptations enable long, autonomous, stealthy flights that are perfectly connected to the Israeli military infrastructure. By combining an advanced tactical approach with cutting-edge aeronautical engineering, the F-35 Adir is positioned as a decisive strategic tool. However, budgetary and industrial challenges, as well as the evolution of enemy defenses, now require constant vigilance to maintain its effectiveness. /end

Is it enough? No, it isn't: fact is that the Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal (IsrAF) does not use ALIS, nor will it use ODIN, what you were careful not to mention. Modesty, no doubt.

Coffee Break: Armed Madhouse – The Trouble with ALIS

(12.08.2025)

The F-35 fighter jet is the most expensive weapons program in U.S. history, but one of its biggest failures isn’t in the air — it’s on the ground. The Pentagon’s Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), conceived as an ambitious plan to revolutionize fighter jet maintenance and logistics, collapsed under the weight of bad design, poor coordination, and perverse incentives that reward failure as readily as success. Its troubled successor, the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), has stumbled out of the gate, revealing a deeper, recurring syndrome in U.S. government technology programs — a systemic incapacity to deliver on large-scale, high-cost projects, where failure is not just common but structurally baked into the process. This article uses the rise and fall of ALIS, and ODIN’s faltering replacement effort, to illustrate how that syndrome operates and why it persists.ALIS’s collapse was not the result of a single flaw but of compounding failures that undermined it from conception to deployment. Conceived as the digital nervous system of the F-35 program, ALIS was meant to track parts and maintenance in real time, streamline repairs, predict failures before they happened, and connect a global fleet with seamless efficiency. In reality, it became a sprawling, brittle, and chronically unreliable burden. Software updates routinely broke existing functions, maintenance crews spent as much time troubleshooting the system as servicing the aircraft, and pilots were grounded not by enemy action but by bad data and system errors. What was billed as a force multiplier instead became an expensive liability — a case study in how poor architecture, weak oversight, and skewed incentives can cripple even the most critical capabilities.Israel Says No to ALISPerhaps the most telling indictment of ALIS came not from a congressional hearing or a Pentagon audit, but from the operational choices of one of America’s closest military partners. In 2016, when Israel received its first F-35I “Adir” fighters, it declined to connect them to the global ALIS network at all. Instead, the Israeli Air Force built its own independent logistics, maintenance, and mission systems to support the jets. Officially, this decision was framed as a matter of sovereignty and cybersecurity — Israel wanted to ensure that no foreign entity could monitor or interfere with its aircraft operations. Unofficially, it was also an acknowledgment that ALIS, as delivered, could not be relied upon for timely, accurate, or secure sustainment.For a program whose central selling point was a globally integrated logistics backbone, one of its earliest foreign customers effectively voted “no confidence” and walked away, creating a precedent that other partners quietly noted. The Pentagon’s answer to such mounting dissatisfaction was ODIN — a fresh start in name, but as events would quickly show, a system fated to inherit many of the same flaws that doomed ALIS.ODIN: The Replacement That StumbledIn 2020, the Pentagon announced that ALIS would be phased out and replaced by the Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN), a “modern, cloud-native” system promising faster updates, stronger cybersecurity, and a leaner, modular design. But almost immediately, ODIN began exhibiting the same flaws it was meant to fix. Hardware shortages delayed initial deployment, integration with legacy F-35 data pipelines proved more complex than anticipated, and shifting requirements coupled with uncertain funding caused repeated schedule slips. Most tellingly, ODIN’s reliance on a patchwork of government, Lockheed Martin, and subcontractor teams recreated the fractured accountability that had hobbled ALIS from the start.By 2023, the Department of Defense quietly acknowledged that ODIN would not fully replace ALIS for years, and in some cases, the two systems would operate in parallel indefinitely. This hybrid setup perpetuated the very inefficiencies ODIN was supposed to eliminate — maintainers still had to wrestle with multiple interfaces, inconsistent data, and duplicated workflows. In effect, ODIN became less a clean replacement than an ongoing patchwork, weighed down by inherited design flaws, bureaucratic inertia, and the same perverse incentives that rewarded visible activity over actual capability.The Consequences of FailureDespite roughly $1 billion spent on ALIS and hundreds of millions more on ODIN, the F-35 fleet’s mission-capable rate remains stuck at about 55%, far below the 85–90% target. ALIS’s failures—and ODIN’s slow rollout—have contributed to chronic maintenance delays, inflated sustainment costs, and reduced operational availability, undermining the F-35’s ability to meet its core mission requirements.From ALIS to the Bigger Problem: Government Project SandbaggingThe ALIS debacle — and ODIN’s halting attempt at redemption — is not an isolated failure but part of a recurring pathology in large U.S. government technology programs. This broader failure syndrome, which can be called project sandbagging, thrives in environments where perverse incentives reward slow progress, extended timelines, and budget inflation over timely, effective delivery. In such programs, failure rarely harms the contractors or agencies involved; instead, it becomes a pretext for additional funding, prolonged contracts, and diluted accountability. The very complexity that justifies massive budgets also shields programs from scrutiny, allowing delays and underperformance to be reframed as the inevitable costs of “managing risk” in ambitious projects. Too often, progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations rather than delivered capability. ALIS is simply a particularly vivid example of how sandbagging erodes readiness, wastes resources, and normalizes failure — a fate shared by other major Defense Department technology projects.When the Sandbags Are Removed: SpaceX vs. NASA The gap between SpaceX and NASA’s congressionally directed SLS/Orion/EGS program is a rare natural experiment in incentives. Under fixed-price, milestone-based Space Act Agreements, SpaceX fielded Falcon 9/Heavy and Crew Dragon and built multiple Starship prototypes on rapid cycles; NASA, by contrast, has spent over $55 billion on SLS, Orion, and ground systems through the planned Artemis II date, with per-launch production/operations estimated at about $4.1 billion—a cadence and cost structure widely flagged as unsustainable.SpaceX’s COTS/CRS/Commercial Crew work tied payments to verified, operational outcomes (e.g., ISS cargo and crew delivery), with NASA’s own OIG estimating ~$55 M per Dragon seat versus ~$90 M for Starliner. In contrast, Congress required NASA to build SLS with Shuttle/Constellation heritage and legacy contracts — locking in cost-plus dynamics, fragmented accountability, and low competitive pressure. While SLS is designed for deep-space crewed missions and thus faces higher safety margins, its cost and schedule gulf with SpaceX still reflects a stark disparity in structural incentives: one path rewards delivery and efficiency, the other sustains delay and budget growth under the banner of “managing risk.” That disparity is the essence of project sandbagging — a system where progress is measured in notional milestones and funding appropriations, not delivered capability.ConclusionThe failure of ALIS is not a rare mishap — it is a case study in a chronic U.S. government failure mode. It reflects a recurring pattern: fragmented accountability, contractor dominance, risk-averse governance, and illusory milestone-driven progress that substitutes process for performance. Like many federal IT programs, it was built under cost-plus contracts, insulated from disruptive innovation, and allowed to persist despite user distrust and operational dysfunction.The slow, incomplete transition to ODIN has not resolved these flaws — it has entrenched them. ALIS’s legacy is more than the logistical hobbling of the F-35 program; it is a warning that without structural reform in procurement, oversight, and incentives, critical technology projects will continue to sandbag transformation while consuming vast public resources. If future programs — including those now on the drawing board — are to avoid the same fate, the cost of inaction must be understood as measured not just in dollars, but in lost capability.Curbing the entrenched practice of project sandbagging will require reforms that change both the incentives and the accountability structures that sustain it. The following measures address the pattern of incentive and oversight failures that doomed ALIS and now hinder ODIN:

- Tie contractor profit to operational outcomes, not just deliverables.

Move away from cost-plus contracts toward milestone payments linked to verified, in-service performance. This makes profit contingent on the system actually working as promised.- Enforce independent technical audits at multiple project stages.

Mandate third-party verification of progress, functionality, and readiness before approving further funding. Auditors should report directly to Congress or another oversight body, bypassing the program office’s chain of command.- Adopt modular, open-architecture requirements.

Design programs so that components can be upgraded or replaced independently. This reduces lock-in to flawed subsystems and encourages competitive sourcing.- Institute “sunset clauses” for underperforming programs.

Set predefined thresholds for cost, schedule, and readiness; if breached, the program must be re-competed, restructured, or terminated. This makes failure a risk for the implementers, not just the warfighters. /endBy shifting incentives toward timely, functional delivery, these measures would make it harder for stakeholders to profit from delay and under-performance. The F-35’s ALIS and ODIN experience demonstrates what results when such guardrails are absent: costly, drawn-out efforts that erode readiness while delivering far less than promised. That is the central lesson of ALIS and ODIN, and why systemic reform is mission-critical. Until the sandbags are removed, the United States will keep mistaking motion for progress — and paying a premium for failure.

Finally, and to conclude, I recall the words of the former Pakistani ambassador in Washington about the employment restrictions imposed by the Americans to military aircrafts (weapons) [The Diplomat], to which Israelis are not subject.

All of this is very, very far from your claim.

Amarante

Moving on , if sweetie pens a technical rebuttal ( no sweetie it's not what you think ) to this I'm going to shave my head ( no sweetie also not what you think ) & post a photograph here just so sweetie doesn't think I'm lying .( No sweetie it's not what you think ) @Innominate

No, definitly. Update to my previous msgs:Current IAF F-35's are standard F-35A's. The only upgrade is being able to drop their nuke bomb and that's it. Israeli systems won't be upgraded for another year or two. Their EW upgrade is in POD form.

Israel's F-35I Fighter's C4 Systems Enter Production at IAI

Apr 03, 2016

Following a successful testing, the Command, Control, Communications and Computing (C4) systems for Israel’s F-35I ‘Adir’

With system definition, prototyping and testing phases completed, Israel Aerospace Industries' (IAI) is now moving to production the Command, Control, Communications and Computing (C4) systems developed for the Adir - F-35I, Israel's variant of the Fifth Generation Fighter F-35.

The systems developed exclusively for the F-35I by IAI's LAHAV Division are part of IAI's cutting edge ‘tactical C4 architecture‘ introducing unique force multipliers in the modern, networked battle arena. The induction of advanced systems of this type with the Israel Air Force (IAF) combat fleet will enable the IAF to better manage, and rapidly field networked applications that interface with core services, over proprietary protocols developed especially for the IAF.

Using generic communications infrastructure based on the latest Software Defined Radios (SDR), IAI new C4 system developed for the Adir will provide the backbone of the IAF future airborne communications network. This network will offer a dramatic improvement over legacy systems currently operating with the current fleet of 4th Generation aircraft (F-16, F-15).

Based on open system architecture, the new system enables rapid software and hardware development cycles that will also provide more affordable modernization and system support over the platform's life cycle, as systems are required to meet rapidly changing operating environments.

The integration of IAI's C4 systems in the F-35I avionics program represents a major milestone in the introduction of advanced, indigenous capabilities to the multinational F-35 program. Fully embedded into the aircraft integrated avionic system, IAI's new C4 system provides the user the latest, most advanced processing capabilities with relative independence of the aircraft manufacturer.

Part of the F-35I avionic system, the C4 system introduces a new level of freedom for the IAF, as it paves the way for additional advanced capabilities to be embedded in the F-35I in the future.

"This cutting edge avionic system represents an ‘operational quantum leap' in the capability of air power to conduct networked-centric air warfare" said Benni Cohen, General Manager of LAHAV division, "It is part of a major change that takes place once in a decade, which includes the upgrading of 4th Generation systems. This program will be critical to our national security as it represents a shift in air forces' concepts of operations (CONOPS) and operational capabilities."

In the past decade, LAHAV Division is positioned as Israel Aerospace Industries' center of excellence implementing network centric warfare capabilities. The combat proven systems developed by LAHAV are operational on all combat aircraft and special mission platforms as well as in land-based systems of the Israel and foreign air forces. /end

@_Anonymous_

no, i didn’t w rite ze blog.

Thx 2 the original posters.

Rafale export sales > EF export sales.France is repeating history with the Eurofighter, have a dummy spit because you didn't get all of the work share,,,Go it alone with what you have,,,The Rafale was a polished Mirage

Rafale unit price < EF unit price

Rafale cost per hour << EF cost per hour

=> France made the good choice to leave EF consortium.

Polished Mirage ? so F35 is a polished F16, fatter, less agile, far more costier, non fully developped 20 years after first flight.