What Does China Want?

by

Jeanne-Marie Gescher Apr 09, 2018, 3:42 pm

5SHARES

Chinese PresidentXi Jinping. (GettyImages)

Snapshot

- To even begin to reach an answer to that question, one has to understand China’s history and philosophy, and how they have shaped its leaders’ worldview.

Six months ago, addressing a landmark Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, President Xi Jinping declared “a new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics”. Xi also noted that “the wheels of history roll on” and “the tides of the times are vast and mighty”.

The West dismissed the “new era” as yet another party slogan, and the idea of history rolling on as rhetoric. Carefully read, though, Xi’s speech was the expression of an idea of order that, one way or another, is very likely to change the world. Understanding how and why is the question of our time.

“What does China want?” is the question of India’s day, asked by Indians with an understandable focus on tense borders and concerns about trade. Directed at the immediate present and the foreseeable future, it seems to demand a simple answer in the current state of affairs.

In reality, however, the only answers worth having depend upon an understanding of China’s past.

A good place to start is with ‘The Great Learning’, a short text that became the manifesto of a civilisation. Attributed to Confucius (551-479 BCE), it sets out a hierarchy of steps by which a ruler can build a strong and peaceful state, with the people contributing to the order of all.

At the heart of ‘The Great Learning’ are three ideas about knowledge that have become so obvious to China and the Chinese that they scarcely need repetition. The first, core, idea is that knowledge is central to the peace and security of everything, from households, to states, to the world at large. That idea is grounded on a second, and more fundamental idea, that everything in the present has its roots in the past and that, over time, those roots have come to include a lot of branches. The third idea, the consequence of the first and second, is that order requires a hierarchy of responsibility, with a mastery of the root-and-branch knowledge — described as “the investigation of things” — being the critical organising principle.

For China, the earliest past was a founding myth of a brother and sister, Fuxi and Nüwa, the sister rescuing the world from an ocean of water and the brother beginning the process of understanding the mechanics of the skies and the land. Fuxi and Nüwa were followed by a succession of “great men” who gradually uncovered the secrets of the cosmos, including the schedules of the seasons that enabled the people to settle and farm, and in so doing created the foundations of China’s world.

Essential to the discoveries of Fuxi and Nüwa, and those who followed them, was a shamanic idea of order. The goal was to find a way in which human beings could live peacefully and securely with each other within the parameters of the natural world.

The cosmos being so complex, and its changes being a fundamental feature, this would require the application of critical human qualities for observing and perceiving not just the visible but the invisible as well. The development of such qualities was at the heart of the Dao (or Tao), the way. As the qualities were developed, more and more knowledge was accumulated, and the settled world of the fields expanded to include more complex worlds of cities.

At one point, some questioned the shamanic idea of order, suggesting that future order would be best achieved under a single, responsible ruler, who would pursue the Dao for all. The shamans split: some became kings and advisers living in cities; others retreated to the wild world of forests and mountains.

While the Yellow Emperor is the most famous of China’s ancient, mythical, rulers, less well-known ones have equally, if not more, important roots. One was Shennong (2,800 BCE), famed for the fact that he worked among the people. Two others were Yao and Shun (2300-2100) who laboured night and day to deliver order to the people. China’s ideals of equality and hard work have a longer history than communism.

All of China’s earliest rulers faced the challenge of a Yellow River that often, catastrophically, broke its banks. Asking the ancestors for advice, one emperor (Zhuanxu; 2500-2400) was told to limit earth’s chaotic communications with heaven to the emperor alone. The idea of controlling communications for a greater order has a long history in China — as does the idea that man’s role in communications between heaven and earth should be focused on the material here and now.

A later ruler, Yu the Great (2200–2100) spent 13 years surveying every inch of the Yellow River and its surrounding land, and creating a map of nine provinces, each identified by specific geographical features that influenced its course. To this can be traced a Chinese passion for maps and a planning-based order that continues to the five year plans of the present.

In 1046, a new dynastic line of rulers, the Zhou, came to power. Their reign would last longer than any other, albeit divided into an early “golden age” and a later period of decline. The hallmark of the Zhou was a dedication to knowledge-based rule. But as the reach of their rule expanded, including large numbers of cities, whose leaders saw themselves as rulers in their own right, the attention to knowledge became increasingly directed to the acquisition of power.

By 700 BCE, questions about order were rising. Over roughly 500 years (to 221 BCE), as the Zhou state crumbled into a world of competing city states, a “hundred schools of thought” emerged. Some, like the man who composed the Daodejing, the classic text of the Dao, argued that the original shamans had been right about the importance of the natural order. Others, notably Confucius, thought that the mass rapid growth of the past necessitated a new idea of order. His ideas, including ‘The Great Learning’, were intended as a manifesto for an idea of order where the pursuit of the Dao was an ideal, but with more written rites, rituals and written principles required to keep both rulers and the people on track. Others, more concerned about equality, modesty and hard work, advocated a return to Shennong’s simple way of life, with Yao and Shun as models for virtue. Yet another argued that, with the old order unravelling, it was time to focus on strict rules and punishments for everyone’s security.

Advertisement

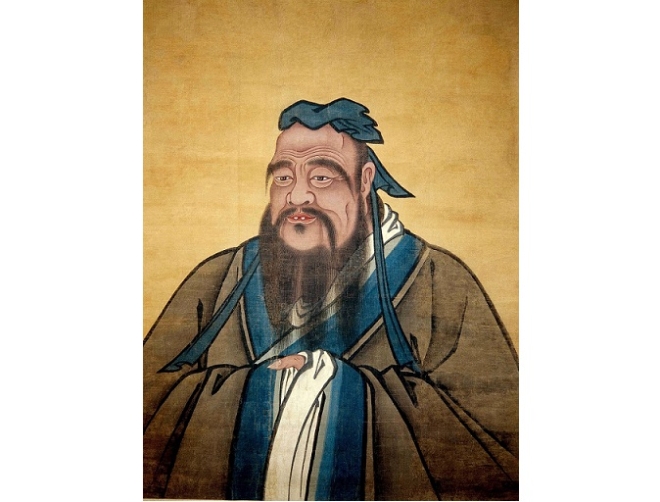

Confucius

At the heart of all of the “hundred thoughts” was a core question of whether man was good or bad. If essentially good, as Confucius argued, rites and rituals would be sufficient to remind him of his responsibilities to wider society. If naturally flawed, however, only strict rules and punishments would work.

Almost all of the branches of today’s competing ideas of order (Chinese ideas and those in the wider world) can be found in this period. They include the branch that led to the 1949 victory of a communism attributed to Karl Marx.

Initially, divided more by ambition than ideals, the competing city states began to go to war. Some 100 in number in 470 BCE, during the roughly 200-year period known as “the warring states”, they would whittle each other down to seven. In the devastating process, new learning would emerge, including inventions in military technology, and the work of a general, Sun, that would come to be known in the West as ‘the art of war’.

From 270 BCE to 221 BCE, the warring states would battle each other down to one. While six of the seven largely adhered to the Confucian idea of “man as fundamentally good”, the seventh, an upstart state of Qin from the wild west, saw man as fundamentally bad. In 221, having spent over a hundred years perfecting a rule grounded in strict laws and punishments, Qin won the war of all against all. Its ruler (the emperor protected by the 10,000 terracotta warriors who survived him), then unified the once-warring states into an empire with, and through, a single language, currency and infrastructure.

Many lessons were learned from the time of the warring states. One was that the decline of a great power (then the Zhou, today the US) raises risks for all. Another was the importance of domestic ideas of order in winning battles with the outside. Yet another was repeated by Xi Jinping in his speech to the 19th party Congress: “History looks kindly on those with resolve”.

While the Qin empire fell to rebels, the subsequent rebel ruler, founder of the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), decided that while Confucian values had their place, strict rules and punishments were also key. Thus began “Confucianism”, the idea of man as “good-ish”: ‘The Great Learning’ for those who were able to learn; the power of the state for those who were not.

The Han restored an agricultural prosperity, but as time passed, three pressures emerged and combined to bring about its end. The first, external, were the steppe tribes to the north, proto Mongols, who coveted the produce of the settled world. The second, internal, was the rise of equality-seeking rebellions. The third, close to the seat of power, was ambitious advisers and generals, whose initial defence of the dynasty ultimately turned them into competing warlords in their own right.

Advertisement

Sunzi

The Han eventually fell to a civil war known as the time of the ‘three kingdoms’ (220–280 CE). Each working with the same ways of thinking (including ‘the art of war’ that a general, Sunzi, had written early on in the time of the warring states), all three competing rulers struggled to find the new idea that would break the deadlock. One discovered a man, Zhuge Liang, whose devotion to the old shamanic ideas had given him extraordinary powers of observation and insight. Zhuge Liang’s strategies became the stuff of legend, inspiring centuries of Chinese, rulers and people alike. Grounded in an intense meditation on the forces of nature, it included an asymmetrical way of thinking that continues to influence policy today.

Not long after the civil war of the ‘three kingdoms’ ended, the first of what would be a succession of competing northern challengers descended. An era known as the “sixteen kingdoms” (304–439 CE) followed, succeeded by the divide of China itself, in an era known as the “northern and southern synasties” (420–589).

While the Tang dynasty would reunify the lands, from 907 CE, another succession of northern challengers would appear, culminating in the conquest of the Mongols and a Mongol Yuan dynasty that would rule for 100 years, before collapsing into rebellions that forced a Mongol retreat. The Ming dynasty would reunite the Chinese lands under Chinese rule but in 1644, they too would fall to the latest power from the North, the Manchu, who called themselves the dynasty of the Qing.

“Why so many repeated conquests?” was China’s biggest question of itself. The two leading answers were the attractions of a settled order that delivered economic wealth on the one hand, and the inevitable rebellions that followed an unequally divided wealth on the other. External threat and internal order were seen as complementary and critical features that determined the security of the state. It was a view that would be confirmed when the Taiping rebellion (1854–64) and the arrival of armed foreign imperial powers (from 1839) brought about the gradual collapse of the Manchu Qing dynasty, culminating in the “first” revolution of 1911.

Like the warring states period, however, that fall brought its own learning. With ‘The Great Learning’ ideal pulling China’s greatest minds into the state bureaucracy, by the mid 19th century, technical innovation had declined to the point that the late Qing state was unable to defend itself against both external and internal threats. At one critical point in the Taiping rebellion (often seen as a civil war), the Qing called upon a senior official with no military experience to raise a local army. When the official raised an army that delivered a decisive victory, a number of Chinese, officials and otherwise, began to think about saving their country themselves.

Some turned to rebellion; others decided to learn as much as they could about the science and technology that the West was using to such powerful effect in its Opium wars. Starting with an arsenal (scouted by one of the first Chinese to go to America, at the height of the American Civil War), bit by bit, they began to rebuild a country decimated by the Taiping rebellion. In so doing, they drew on the fundamental great learning principle that knowledge is everything, and on the longstanding convictions that endurance, hard work and asymmetrical thinking were essential to success. Driven by the deep love of a land that was not just a country but a civilisation, many of them came to be seen as heroes.

Chinese leader Mao Tse-tung (1893-1976), accompanied by his second-in-command Lin Biao (1907-1971), passes along the ranks of revolutionaries during a rally in Tiananmen Square, Peking (Beijing), 1966. (Keystone/Getty Images)

The Qing eventually fell by accident — a bomb-in-the-making that accidentally exploded in a provincial capital, whose secret revolutionaries included many officers and men serving in the imperial army. Anticipating discovery, the revolutionary officers advanced their plans and declared a state of independence that was swiftly followed by other provinces. As China began to look as if it would divide again, a cunning general brokered the abdication of the last Qing emperor, the declaration of a republic and the hurried transfer of power to a national assembly — with no time for a constitution. Within two years, the general, Yuan Shikai, had become president of the assembly; within a year after that, he dissolved the assembly, observing that the whole idea had been a mistake: “too many arguments; not enough results”. Briefly declaring himself emperor of a new “Chinese empire”, his early (natural) death opened the way to a new era of competing warlords.

For many, including the Chinese Communist Party, the aftermath of the 1911 revolution is a textbook example of the risks of democratic ideals without careful attention to the mechanics of order. When Chinese lands once occupied by Germany were passed to Japan at the end of the First World War, the lesson of internal order was seen to have been taught again. Another lesson, learned not for the first time, was the factional risks of armies.

In 1927, China was plunged into a civil war, triggered by a massacre of communists led by the leading internal power, the Nationalist Party, Guomindang. By 1934, the Communist Party would be led by Mao Zedong, an unlikely candidate at the outset, but one who had seen the possibility of combining a number of powerful ideas, both foreign and Chinese.

Mao’s ideas that were easiest for the West to understand were those that came from the West: primarily Marx’s idea of economic determinism. Less familiar were the organising principles that Lenin had designed for the purposes not just of winning a revolutionary battle but of maintaining revolutionary success. Far less visible were the lessons on resolve, taught by the Qin victory within the warring states; the importance of asymmetrical thinking, taught by Zhuge Liang; and the ancient belief in a golden utopia where a ruler would work as hard as his people, and all men would be equal.

Experimenting with the idea of order, Mao’s rule was controversial to say the least (even less visible to the West was Mao’s love of the Monkey King, a character created in the 16th century, who delights his readers with an earthy irreverence, and managed to confound even heaven with his supernatural powers). With the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution leaving China’s economy in rubble, today, the Communist Party considers Mao to have been “70 per cent right, 30 per cent wrong”. But internal unity had been established, and foreign powers had been repelled.

Included in that process was a “clarification” of Sino-Indian borders in the Himalayan boundaries of Tibet, that had come to hold critical strategic importance to the Chinese state. It was in 1962 that the tenth Panchen Lama (the highest ranking Buddhist teacher after the Dalai Lama, who had already left Tibet for India) wrote a secret memorandum to Mao, protesting at the price of unifying China and Tibet. Rightly or wrongly, in 1962, managing Tibet’s borders would have been seen as a matter of internal security.

China’s different ideas of order had already been seen by the West as a problem to be addressed. In 1958, secretary of state John Foster Dulles had officially committed the US to transforming China’s state-led socialism to popular democracy through a policy of “peaceful evolution”. Mao took exception, as have all Chinese leaders thereafter. Any dreams of trust vanished, and while economic globalisation would later gloss over the differences, the American idea of a mission to change China continued — until today, when the idea has become more of an inquest into how the mission failed.

Deng Xiaoping

Following Mao, Deng Xiaoping focused on repairing China’s broken economy. With five decades of his own guerilla thinking under his belt, he declared that “it doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white as long as it catches mice”. Attention focused on four key modernisations. The most important — the science and technology first identified by the 19th century self-strengtheners — ran through all the other three (agriculture, defence and industry).

Confronted with the contradiction of a communist party pursuing economic growth with both capitalist and socialist measures, Deng went back to the roots of communism. He explained that China had gone from feudalism to socialism too quickly, erroneously skipping Marx’s capitalist stage. The capitalist West (initially, particularly the highly successful overseas Chinese) was then invited to invest not just capital but technology in ring-fenced special economic zones (SEZs). Everyone’s energies unleashed (Chinese and foreign), the SEZs became rapidly expanding cities (a fishing village in 1978, Shenzhen, whose name means “deep ditch”, now has a gross domestic product (GDP) of almost $300 billion). The power of asymmetrical thinking was proven once again.

Over the following three decades, Deng and his successors rebuilt the Chinese state. In the process, they raised a mass rapid economic development that astonished the rest of the world. To asymmetrical thinking was added a deliberation that was grounded in the great learning conviction that a painstaking commitment to root-and-branch knowledge was everything. Five year plans began the day after each previous one had been completed: long-term plans were made for science and technology. A policy commitment to infrastructure led to a combination of state- and non-state investments, creating not only some of the most valuable transport and urban assets in the world but entirely new infrastructure-focused industries that have stretched the limits of nature and, whether directly or by replication, changed the maps of many other parts of the world.

At the same time, a new generation of self-strengtheners emerged, seeing themselves as complementing Deng’s reforms, and appearing as entrepreneurs. They included the founders of online businesses that now compete not only with Amazon, Facebook and Google, but increasingly with the artificial intelligence and quantum computing ambitions of the US-led West.

While many of China’s projects have been controversial, few countries in the world have not sought to emulate its “miracle”. Most assume that it is all about a magic set of economic policies. They are wrong.

By 2012, those to the right of party were happy, while those to the left saw a revolution betrayed. China had become one of the most unequal countries in the world (Gini coefficient of 0.49) and the poorer population was remembering Mao’s promises of equality. Added to this, the legacy of Deng’s exhortation to the party to maintain a modest profile as it rebuilt the country, had led to an increasing gap between China’s rising economic strength and its limited participation in the mechanics of the global order.

At this point, and perhaps not surprisingly, Xi Jinping, the first Chinese leader to have been born into and grown up within the party, and the only leader to have headed the party’s central school (a combination of a wide-ranging think tank and a political academy, which pursues its great learning not only in the roots and branches of China’s story but in the story of the world at large), came to power.

What does China want? If one takes a look at the last five years through the roots and branches of the past, it is reasonably clear.

Immediately upon coming to power in 2012, and with the party’s primacy increasingly being questioned, Xi declared a dream of a great rejuvenation of China. Within a year, almost certainly referencing not only China’s history but Alexis de Tocqueville’s

The Old Regime and the Revolution (the greatest time of danger for a state is when it reforms), Xi launched both a mass line campaign and an anti-corruption drive.

Invented by Mao, the mass line is a sustained process of engagement and reflection directed to winning the critical battle for a public opinion. A tool of many new leaders, the anti-corruption campaign was designed to address not only corruption, but factionalism and anticipated opposition to new policy ideas.

Both campaigns included a strong focus on public examples of the kind of modesty and hard work that Yao and Shun had long ago established.

In late 2013, Xi set out key policies for his first term of office. While the policies referenced some of the West’s hoped-for economic liberalisation, they also set out the most comprehensive plan for reform ever put forward: economic, political, legal, military, social, cultural and ecological. Supported by a new leading group for comprehensively deepening reform, year by year, Xi proceeded to lay the foundations of the dream described.

For an India concerned with borders, relevant reforms included a restructuring of the military, a concept of a “common community of destiny”, that would begin to add Chinese ideas to the old Western global order, and a Belt and Road that would take China’s accumulated experience in infrastructure-based development to the wider world. They also included a commitment to becoming a modern socialist country that would take its place as a world leader by 2049, the hundredth anniversary year of the 1949 revolution.

For an India concerned with trade, with a strong interest in software, and an increasing role in global growth, the reforms included a powerful focus on science and innovation, with an Internet Plus and a Made in China 2025 that would integrate the internet with traditional manufacturing to transform the economy. Xi noted that China’s biggest advantage as a socialist country was its ability to “pool resources in a major mission”.

Other commitments included achievement of a

xiaokang, moderately well-off society by 2021, global leadership in innovation by 2035, and the promotion of an “ecological civilisation” to address the roots and branches of environmental challenge, including climate. Meanwhile, the party made it clear that the socialist market economy is about markets with Chinese ideas of order.

Understanding, as Sunzi’s ‘Art of War’ would tell you, is not endorsement. Quite the contrary, understanding is essential to the great learning that enables states and people to navigate their way through a world that is constantly changing, even if we can’t always see and appreciate the change at the time that it is happening.

At the end of his party speech in late 2017, Xi noted that both China and the world are in the midst of profound and complex changes. Few could disagree with that. While the US-led West asks itself how it “lost” China, other countries might take a look at China’s roots and branches and think not just about what China wants, but why it wants it.

Change is certainly here. As Zhuge Liang would say, what matters is how we see it.

What Does China Want?