Quantifying India and its foreign relations through media monitoring

In September 2022, India became the fifth largest economy in the world by overtaking the United Kingdom, according to a recent report from the International Monetary Fund. India’s economic and political rise has both domestic and global implications and might alter the nature of the country’s foreign relations with powerful countries like the United States, China, and Russia, and vice versa. Furthermore, global events, such as the protectionist tech policies imposed by former President Trump on Chinese trade policies, the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the deepening of authoritarianism in China, are forcing global realignment. Consequently, countries like India are reassessing their foreign relations with existing major powers and signaling interests and preferences vis-à-vis new emerging powers.

In this essay, we quantify India’s foreign relations based on news that involves the country and the top economies in the world: Australia, China, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, the United States, and Russia. We exploit the Global Database of Society

, which is a part of the

Global Data on Events, Location, and Tone (GDELT) Project that monitors news (broadcast, print, and digital) across the globe in more than 65 languages. Within 15 minutes of a news event breaking worldwide, the GDELT Project translates the event if it is in a language other than English and processes the news to identify the event, location, people, and organizations involved and the nature and theme of the event based on more than 24 emotional measurement packages (the largest deployment of sentiment analysis) to assess more than 2,300 emotions and themes to “contextualize, interpret, respond to, and understand global events” in near real-time.

The GDELT database lends itself to fascinating quantitative analysis of the changing nature of international relations as reflected in the news and media coverage. In our analysis, we find significant changes in India’s bilateral relations with major economies like France, China, Russia, and the United States in recent years. We also find structural breaks and major realignment in the relations of global powers vis-à-vis China since 2018.

Research methods

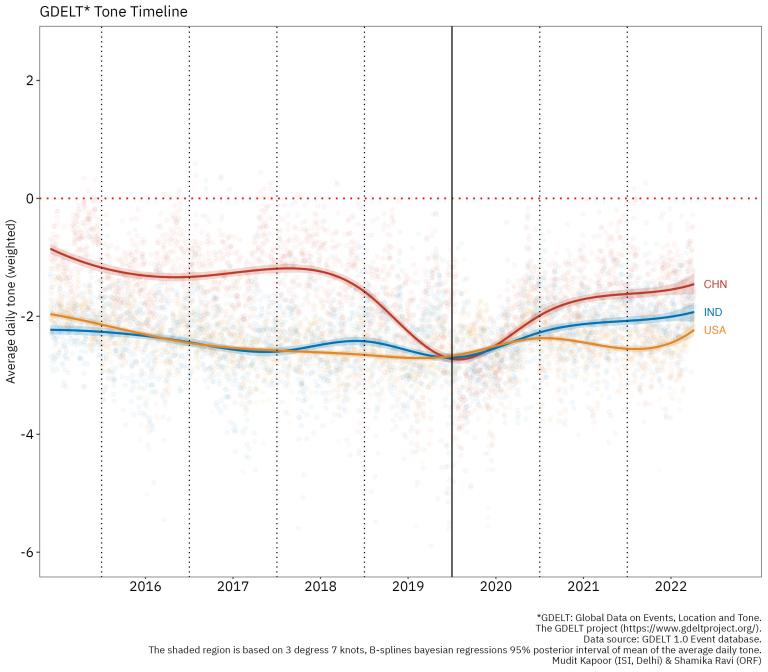

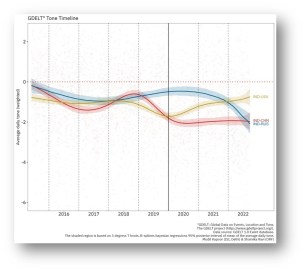

We limit our analysis to the GDELT event database that records events (such as appeals for rights, ease of restrictions on political freedoms, protest, etc.), the date of the event, and the actors involved (which could be geographic, ethnic, religious, etc.), the country of the actors, the number of mentions of the event (the higher the mentions, the more important the event), and the average media tone associated with the event, which is a numeric value that can range from -100 (extremely negative tone) to +100 (extremely positive tone), with typical values between -10 and +10 and with zero indicating a neutral event. Our analyses focus on events from June 15, 2015, to September 24, 2022. Overall, we analyze more than 99 million events, where the major actors were from three large countries: India, China, and the United States. We also estimate an average daily tone for each of the three countries by constructing a weighted mean of the average tone of all the events recorded on that date, with the number of mentions as a weight for each event. Our primary objective is to identify the pattern of the daily weighted average tone of the events related to India, China, and the United States from 2015 to 2022. To achieve this, we fit a Bayesian regression with a cubic spline and seven knots and plot the posterior mean with 95% intervals of the weighted average daily tone.

Media Tone: China vs. USA vs. India

Overall, we find that events related to China, an authoritarian country with severe restrictions on free media, have a relatively more positive tone than the tone of events in democracies such as India and the United States. However, since 2018, the tone of events related to China has begun a sharp downward trend. This change toward China was also observed in

a 2021 Pew survey on Americans’ views toward China. It is also interesting to note a more positive trend in tone for India-related events since 2020, which remains steady and does not exhibit any sharp pattern.

(i) India’s relations with the United States, China, and Russia

In our analysis of events related to India, China, the United States, and Russia, we focus on events where the prominent actor is India. Until late 2021, events related to India and Russia had a relatively more positive tone than those associated with India and the United States. and India and China. However, since late 2021, there has been a sharp reversal in the tone of events related to India and Russia. This is most likely a direct outcome of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

We also find that the tone of events related to India and China had a sharp reversal during the Doklam crisis in 2017 when there was a military border standoff between the Indian Armed Forces and the People’s Liberation Army of China. This was in response to the Chinese constructing a road at the trijunction area of India-Bhutan-China. The border standoff lasted more than two months and ended only when the Chinese halted the road construction and troops from both sides withdrew from Doklam. There was a short recovery in late 2018, however, from early 2019 onwards, there has been a sharp reversal in tone which worsened at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Thereafter, India-China relations have continued to remain steady but at a historic low.

Concerning events related to India and the United States, we observe that their tone was steady and continuous until the middle of 2018, after which it started to fall. This downward trend continued until 2020 (the year of U.S. elections and the start of the pandemic), after which we observe a steady rise in the tone of events related to India and the United States.

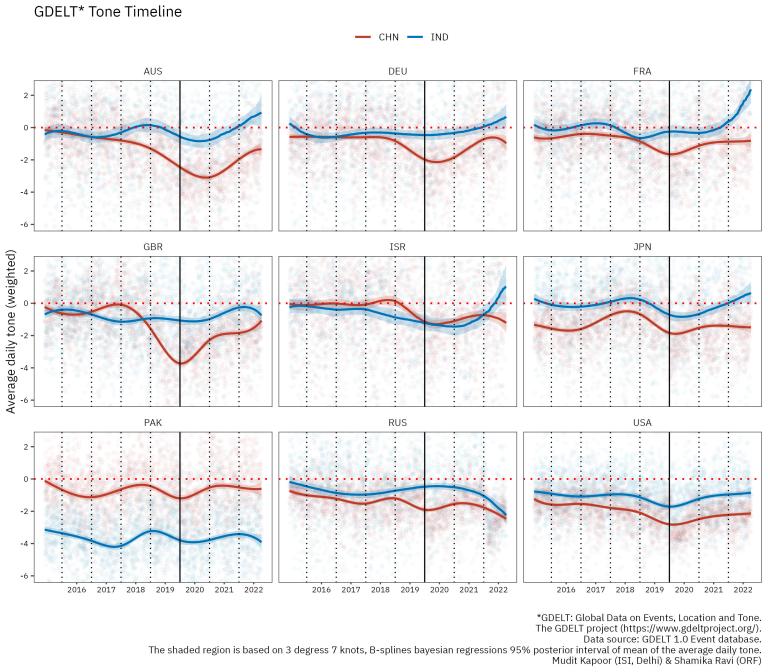

(ii) Global realignment: China v. India

In our analysis, we also reviewed events that relate India and China to the world’s top economies: Australia, China, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, the United States, and Russia. We include Pakistan (PAK) and Israel (ISR) for this analysis, as both countries are important actors in India’s foreign policy.

Over the entire period, the average tone of events that relate India to the major economies has remained somewhat similar, except for France and Israel, where there is a significant upward swing in the average tone after 2021. Not surprisingly, this reflects the dramatic improvements in India’s ties with Israel and France in recent years.

In contrast, since 2018, the average tone of events that relate China to the major economies has experienced a downward trend. In particular, the India-China gap in the average tone with Australia, Germany (DEU), France, and the United States widened after 2018. However, since 2020, the downward trend in the average tone of events has either reversed or remained constant. The most striking result of this analysis concerns Russia’s relations with India and China. We observe a sharp downward trend in the tone of events concerning Russia’s relations with both China and India between 2021 and 2022, which is most likely the outcome of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Broadly, the average tone of events that relate India to the major economies is higher compared to events that relate China to the major economies (in particular, Australia, Germany, France, and the United States); this gap has widened since 2018-2019. Results for Pakistan are along expected lines, as the tone of events covering its relations with China and India remain steady and unaffected by global events over time. Pakistan’s relations with China are significantly better than its relations with India, which have a systematic and significant negative tone.

Conclusion

The findings of our research suggest that events related to China (which has heavy-handed, authoritarian restrictions on all forms of media) have a relatively more positive tone than large federal democracies when it comes to media, such as India and the United States, which have a relatively free press. However, since 2018-2019, there has been a sharp downward trend in tone of events related to China, perhaps reflecting the changing view of China in the western world, particularly within the United States, and the former president’s political attack on China concerning its trade policy. However, in the last two years, we have observed a reversal in this trend, which could reflect an easing of the tension post-pandemic and change in the U.S. government.

When analyzing events that relate India and China to the top economies and Russia, we find a widening gap in the average tone of events. However, when it comes to Russia post-2021, there has been a sharp decline in the average tone of events for both China and India, perhaps an outcome of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Based on the average tone of events, the findings suggest a consistent realignment of the world’s top economies in their foreign relations concerning India and China, especially after 2018.

A quantitative analysis of India’s foreign relations based on news that involves the country and the top economies in the world.

www.brookings.edu