First integrated battle group to be deployed along India-Pakistan border

- Thread starter _Anonymous_

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

In the next few weeks, the Indian army's Mountain Strike Corps will go into 'battle' across its intended area of deployment-the Himalayas. In the first exercise since its raising in 2014, the Ranchi-based 17 Corps will launch three Integrated Battle Groups (IBGs)-brigade-sized formations backed by medium artillery, helicopters, tanks and armoured personnel carriers in simulated thrusts across the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The manoeuvres will be far away from the currently taut and violent Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan, but not too distant from Doklam, where India and China ended a 72-day military stand-off in 2017.

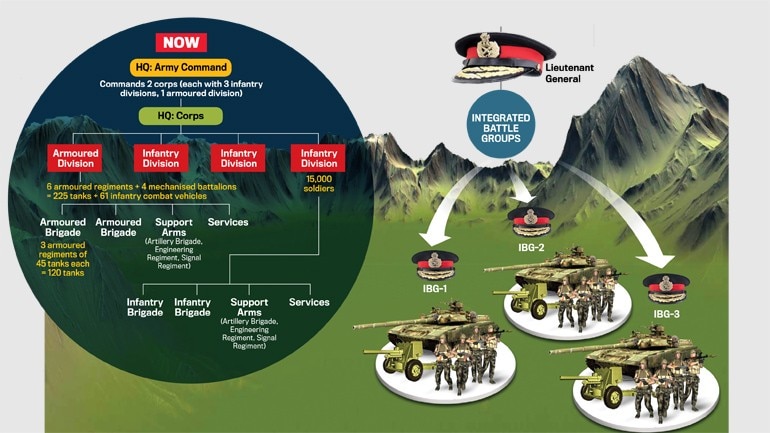

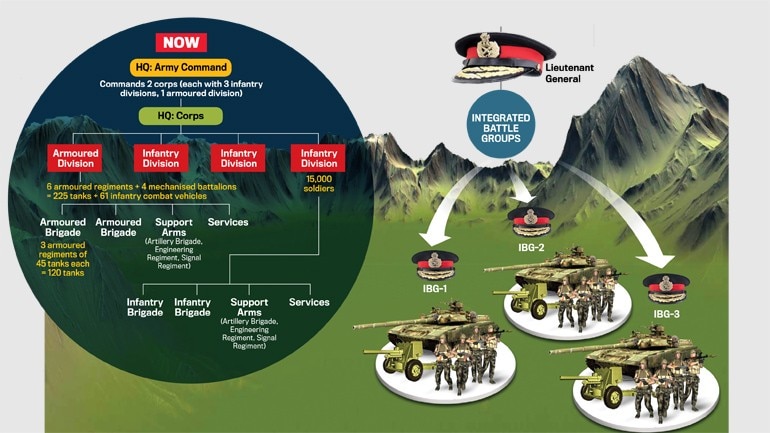

Army chief General Bipin Rawat and his generals will watch the exercise very carefully because it validates several concepts they have worked on for months. The chief is betting big on IBGs-lean mobile formations consisting of 5,000 soldiers, backed by artillery and armour-to become the army's force of the future. It is the biggest restructuring of a force that has continued almost without any reorganisation since Independence.

Senior army officials say the exercise, the first of its kind in the northern theatre, respects the April 2005 protocol with China, which urges both sides to 'avoid holding large-scale military exercises involving more than one division (approximately 15,000 troops) in close proximity to the LAC'.

The exercise, which is yet to be given a name-army officials say this is to maintain secrecy-is to be held at altitudes of over 10,000 feet. It will also validate the army's ability to launch manoeuvres in the mountains using its only strike corps under the Eastern Command. The three Mountain IBGs have been carved out of the 17 Corps' Panagarh-based 59 Mountain Division. From its base in Ranchi the Corps HQ will control the exercise that is in the planning stages for several weeks. Details of the exercise are secret, but military tacticians say the battle groups could be expected to do one or more of the following: interdict a strategic highway, make an initial bridgehead for launching further offensives, seize an area posing a threat to the Chumbi Valley or launch an offensive across a frozen river to capture posts.

Betting big on IBGs

Ever since the downward spiral in relations with Pakistan in 2016, the Indian army has been restocking missiles, tank and artillery ammunition to be able to fight a 10-day intensive war, or what it calls '10(I)' scales. The Director General of Military Operations (DGMO), the army's principal war planner, has begun studying the terrain from Jammu and Kashmir to the Rann of Kutch to see how IBGs can be deployed.

"You don't announce a war," Gen. Rawat tells India Today when asked whether a conflict with Pakistan is now a more probable option than it was in recent years. He emphasises the element of surprise. "Nobody would want to go to war, but if the (situation) were to go out of hand, we won't hesitate to do some limited action," says the army chief. 'Out of hand' is a clear reference to an act of grave provocation. For instance, a mass-casualty terrorist attack originating from across the border?

The adversary, Gen. Rawat acknowledges, is 'unpredictable'. "And unpredictable is a very sober word if you see the kind of statements that are coming from Pakistan these days," he says. The army chief hopes to have about a dozen IBGs along the western border with Pakistan "in the next four to five years". The aim is for IBGs to break through the adversary's defences and cross the border in hours, not days as was the practice earlier. The objective is to capture territory and create 'launchpads' inside enemy territory for the main body of troops to join in.

Even as the 17 Corps is readying for its mountain manoeuvres, the 9 Corps, based in Yol, in the Himalayan foothills near Dharamsala, has been earmarked for restructuring. One of the corps falling under the Chandimandir-based Western Command will be broken up into three IBGs. The IBGs will be positioned along the international border with Pakistan.

The IBGs will be sector- and terrain-specific. No two IBGs will be alike. "From one-size-fits-all, we are moving towards sector- and terrain-specific IBGs," says Gen. Rawat. The IBGs will be guided by what he calls 'TTTR'-Threat, Terrain, Task and Resources. The resources of an IBG-the number of tanks, artillery pieces, bridging equipment it carries-will be guided by its task, terrain and the threat it faces. In the strongly-defended plains of Pakistan's Punjab province, Indian IBGs can expect stiff resistance from heavy and light anti-tank units and infantry entrenched behind ditch-cum-bunds (DCBs). They will need tanks, anti-tank weapons, armoured personnel carriers and close-air support from the IAF's newly acquired AH-64E Apache tank-busting helicopter gunships. In the Rajasthan desert, where resistance is unlikely to be as stiff, the threat will come from enemy tanks and anti-tank units.

IBGs are one of the most important aspects of Gen. Rawat's plan to retool army formations for a collusive military threat from China and Pakistan. The proposal for IBGs will shortly be sent to the government. The battle groups could replace the army's basic 'all-arms' unit-the infantry division. The division, which consists of between 15,000 and 18,000 soldiers and includes other arms like artillery brigades, helicopters and signal and engineering regiments, has been found to be ponderous and slow-moving. It takes days to be mobilised. Strategy, as Napoleon said, is the art of making use of time and space. Using the IBG strategy, the army plans to capture enemy territory within hours, not days.

A strategic move

The restructuring plan was initiated with four studies last year, each headed by a lieutenant general, with the aim of reconstituting the field army, reducing personnel from the army headquarters and reviewing the terms of engagement of officers and soldiers. The larger aim is to pare off up to 100,000 personnel and use the savings to boost the army's capital budget, what it uses to buy new equipment.

With IBGs, the army hopes to address a long-standing weakness-the inability to inflict punitive strikes against the Pakistan army. It also has the backing of a political leadership unafraid of calling Pakistan's nuclear bluff like it did when it carried out the air strike in Balakot on February 26. Until 15 years ago, the army operated under what was called the Sundarji doctrine, propounded by its former chief in the late 1980s: seven defensive corps that held the border with Pakistan and three offensive 'strike' corps brought in from inland. The first cracks in the doctrine appeared in 2001. It took the army over 20 days to deploy its strike corps to the border following the December 2001 terror attack on Parliament. The army believes this ponderous deployment cost them the element of surprise at a time when Pakistan had not laid minefields and its own strike formations were far away from the border.

The Cold Start doctrine, unveiled by the army in 2004, called for defensive corps to carry out shallow cross-border thrusts within 72 hours. The thrusts were given limited objectives, such as capture of territory. Deep thrusts, it was feared, would force Pakistan to launch nuclear weapons. The plans were, however, never implemented until Gen. Rawat came on the scene in 2016. Even as it war-gamed Cold Start in multiple exercises over the years, the army did not create IBGs. It opted for ad hoc battle groups taken out of the strike corps coming together and exercising on the border just days prior to the offensive. This did not achieve the objectives of having them fight as a cohesive, integrated unit. Even the 72-hour window proposed by Cold Start began rapidly closing when Pakistan began moving its forces closer to the border.

The solution, Gen. Rawat believed, was to have a force that was stationed as an integrated unit near the border, complete with armour, artillery, combat engineers and signal units. These would be like the basic fighting formation in the US-the Stryker Brigade Combat Team. Every Stryker brigade has 4,500 soldiers and over 300 armoured vehicles. The IBGs, the army proposes, will strike across the border in less than 24 hours. The army will evaluate the results, converting some of its 40 infantry divisions into IBGs before it expands the scope.

This year marks the 30th anniversary since the army increased its strength in Jammu and Kashmir to fight Pakistan-backed insurgency. The low intensity conflict operation (LICO) and the disputed borders with Pakistan and China in J&K have drawn in close to a third of the 1.3 million-strong army. The large army presence is also to guard the disputed boundaries with China and Pakistan. The impact has been what analysts call 'LICO-isation' of the army, where the force is drawn away from its primary task of fighting external aggression.

Out of the box

Proponents of 'shock and awe' say creating IBGs amounts to diluting the power of the army's strike corps for limited gains. "You are recasting your sledgehammer, called the Strike Corps, into 20 smaller hammers to fight smaller, localised defensive battles near the border. Where is the coercive edge? How are you challenging Pakistan's strategic depth?" asks Lt General P.S. Mehta, former deputy army chief.

THINKING AHEAD Army chief Gen. Bipin Rawat (Photo: Waseem Andrabi/Getty Images)

Military analysts see in the IBG concept a chance to make the army's ponderous organisations lean, agile and flexible on the battlefield. It provides the army an opportunity to regain its balance in composition of organisation, equipment and quality of leadership and a refreshing change from a heavy infantry skew to the combined arms approach. "IBGs will demand greater dynamism, boldness, initiative and risk-taking ability from our military leadership, which has not been evident in the recent past," says Lt General P. Ravi Shankar, former director general, artillery. "It also demands knowledge, understanding and execution of an all-arms concept, which has been diluted by large sections of the infantry that view counter-insurgency as the prime and only operational area of expertise required."

"The biggest challenge the IBGs will face will be the Pakistani mechanised forces-tanks and anti-tank forces. Another hurdle will be logistics-fuelling our fast-moving columns and resupplying them with ammunition as they fight intense battles in a fluid battle-space," says Brigadier Kuldip Singh (retd), former principal director (defence) in the National Security Council Secretariat.

These are questions that will be asked as the first IBGs take off later this year. Their success will be key to determining whether the Indian army will achieve greater agility or be condemned to a jumbo-sized existence.

The new strike strategy

Army chief General Bipin Rawat and his generals will watch the exercise very carefully because it validates several concepts they have worked on for months. The chief is betting big on IBGs-lean mobile formations consisting of 5,000 soldiers, backed by artillery and armour-to become the army's force of the future. It is the biggest restructuring of a force that has continued almost without any reorganisation since Independence.

Senior army officials say the exercise, the first of its kind in the northern theatre, respects the April 2005 protocol with China, which urges both sides to 'avoid holding large-scale military exercises involving more than one division (approximately 15,000 troops) in close proximity to the LAC'.

The exercise, which is yet to be given a name-army officials say this is to maintain secrecy-is to be held at altitudes of over 10,000 feet. It will also validate the army's ability to launch manoeuvres in the mountains using its only strike corps under the Eastern Command. The three Mountain IBGs have been carved out of the 17 Corps' Panagarh-based 59 Mountain Division. From its base in Ranchi the Corps HQ will control the exercise that is in the planning stages for several weeks. Details of the exercise are secret, but military tacticians say the battle groups could be expected to do one or more of the following: interdict a strategic highway, make an initial bridgehead for launching further offensives, seize an area posing a threat to the Chumbi Valley or launch an offensive across a frozen river to capture posts.

Betting big on IBGs

Ever since the downward spiral in relations with Pakistan in 2016, the Indian army has been restocking missiles, tank and artillery ammunition to be able to fight a 10-day intensive war, or what it calls '10(I)' scales. The Director General of Military Operations (DGMO), the army's principal war planner, has begun studying the terrain from Jammu and Kashmir to the Rann of Kutch to see how IBGs can be deployed.

"You don't announce a war," Gen. Rawat tells India Today when asked whether a conflict with Pakistan is now a more probable option than it was in recent years. He emphasises the element of surprise. "Nobody would want to go to war, but if the (situation) were to go out of hand, we won't hesitate to do some limited action," says the army chief. 'Out of hand' is a clear reference to an act of grave provocation. For instance, a mass-casualty terrorist attack originating from across the border?

The adversary, Gen. Rawat acknowledges, is 'unpredictable'. "And unpredictable is a very sober word if you see the kind of statements that are coming from Pakistan these days," he says. The army chief hopes to have about a dozen IBGs along the western border with Pakistan "in the next four to five years". The aim is for IBGs to break through the adversary's defences and cross the border in hours, not days as was the practice earlier. The objective is to capture territory and create 'launchpads' inside enemy territory for the main body of troops to join in.

Even as the 17 Corps is readying for its mountain manoeuvres, the 9 Corps, based in Yol, in the Himalayan foothills near Dharamsala, has been earmarked for restructuring. One of the corps falling under the Chandimandir-based Western Command will be broken up into three IBGs. The IBGs will be positioned along the international border with Pakistan.

The IBGs will be sector- and terrain-specific. No two IBGs will be alike. "From one-size-fits-all, we are moving towards sector- and terrain-specific IBGs," says Gen. Rawat. The IBGs will be guided by what he calls 'TTTR'-Threat, Terrain, Task and Resources. The resources of an IBG-the number of tanks, artillery pieces, bridging equipment it carries-will be guided by its task, terrain and the threat it faces. In the strongly-defended plains of Pakistan's Punjab province, Indian IBGs can expect stiff resistance from heavy and light anti-tank units and infantry entrenched behind ditch-cum-bunds (DCBs). They will need tanks, anti-tank weapons, armoured personnel carriers and close-air support from the IAF's newly acquired AH-64E Apache tank-busting helicopter gunships. In the Rajasthan desert, where resistance is unlikely to be as stiff, the threat will come from enemy tanks and anti-tank units.

IBGs are one of the most important aspects of Gen. Rawat's plan to retool army formations for a collusive military threat from China and Pakistan. The proposal for IBGs will shortly be sent to the government. The battle groups could replace the army's basic 'all-arms' unit-the infantry division. The division, which consists of between 15,000 and 18,000 soldiers and includes other arms like artillery brigades, helicopters and signal and engineering regiments, has been found to be ponderous and slow-moving. It takes days to be mobilised. Strategy, as Napoleon said, is the art of making use of time and space. Using the IBG strategy, the army plans to capture enemy territory within hours, not days.

A strategic move

The restructuring plan was initiated with four studies last year, each headed by a lieutenant general, with the aim of reconstituting the field army, reducing personnel from the army headquarters and reviewing the terms of engagement of officers and soldiers. The larger aim is to pare off up to 100,000 personnel and use the savings to boost the army's capital budget, what it uses to buy new equipment.

With IBGs, the army hopes to address a long-standing weakness-the inability to inflict punitive strikes against the Pakistan army. It also has the backing of a political leadership unafraid of calling Pakistan's nuclear bluff like it did when it carried out the air strike in Balakot on February 26. Until 15 years ago, the army operated under what was called the Sundarji doctrine, propounded by its former chief in the late 1980s: seven defensive corps that held the border with Pakistan and three offensive 'strike' corps brought in from inland. The first cracks in the doctrine appeared in 2001. It took the army over 20 days to deploy its strike corps to the border following the December 2001 terror attack on Parliament. The army believes this ponderous deployment cost them the element of surprise at a time when Pakistan had not laid minefields and its own strike formations were far away from the border.

The Cold Start doctrine, unveiled by the army in 2004, called for defensive corps to carry out shallow cross-border thrusts within 72 hours. The thrusts were given limited objectives, such as capture of territory. Deep thrusts, it was feared, would force Pakistan to launch nuclear weapons. The plans were, however, never implemented until Gen. Rawat came on the scene in 2016. Even as it war-gamed Cold Start in multiple exercises over the years, the army did not create IBGs. It opted for ad hoc battle groups taken out of the strike corps coming together and exercising on the border just days prior to the offensive. This did not achieve the objectives of having them fight as a cohesive, integrated unit. Even the 72-hour window proposed by Cold Start began rapidly closing when Pakistan began moving its forces closer to the border.

The solution, Gen. Rawat believed, was to have a force that was stationed as an integrated unit near the border, complete with armour, artillery, combat engineers and signal units. These would be like the basic fighting formation in the US-the Stryker Brigade Combat Team. Every Stryker brigade has 4,500 soldiers and over 300 armoured vehicles. The IBGs, the army proposes, will strike across the border in less than 24 hours. The army will evaluate the results, converting some of its 40 infantry divisions into IBGs before it expands the scope.

This year marks the 30th anniversary since the army increased its strength in Jammu and Kashmir to fight Pakistan-backed insurgency. The low intensity conflict operation (LICO) and the disputed borders with Pakistan and China in J&K have drawn in close to a third of the 1.3 million-strong army. The large army presence is also to guard the disputed boundaries with China and Pakistan. The impact has been what analysts call 'LICO-isation' of the army, where the force is drawn away from its primary task of fighting external aggression.

Out of the box

Proponents of 'shock and awe' say creating IBGs amounts to diluting the power of the army's strike corps for limited gains. "You are recasting your sledgehammer, called the Strike Corps, into 20 smaller hammers to fight smaller, localised defensive battles near the border. Where is the coercive edge? How are you challenging Pakistan's strategic depth?" asks Lt General P.S. Mehta, former deputy army chief.

THINKING AHEAD Army chief Gen. Bipin Rawat (Photo: Waseem Andrabi/Getty Images)

Military analysts see in the IBG concept a chance to make the army's ponderous organisations lean, agile and flexible on the battlefield. It provides the army an opportunity to regain its balance in composition of organisation, equipment and quality of leadership and a refreshing change from a heavy infantry skew to the combined arms approach. "IBGs will demand greater dynamism, boldness, initiative and risk-taking ability from our military leadership, which has not been evident in the recent past," says Lt General P. Ravi Shankar, former director general, artillery. "It also demands knowledge, understanding and execution of an all-arms concept, which has been diluted by large sections of the infantry that view counter-insurgency as the prime and only operational area of expertise required."

"The biggest challenge the IBGs will face will be the Pakistani mechanised forces-tanks and anti-tank forces. Another hurdle will be logistics-fuelling our fast-moving columns and resupplying them with ammunition as they fight intense battles in a fluid battle-space," says Brigadier Kuldip Singh (retd), former principal director (defence) in the National Security Council Secretariat.

These are questions that will be asked as the first IBGs take off later this year. Their success will be key to determining whether the Indian army will achieve greater agility or be condemned to a jumbo-sized existence.

The new strike strategy

What does ibg consist.Already deployed.

I mean generalised components

What does ibg consist.

I mean generalised components

Leaving out the airborne component as of now, pretty much everything which we have discussed. Can't get into more details.

@Falcon.. How valid is this statement.. ? I was of the opinion that the Strike corps are not being re-structured.. and these strike corps would be the follow-on forces, once the IBGs make their gains..."You are recasting your sledgehammer, called the Strike Corps, into 20 smaller hammers to fight smaller, localised defensive battles near the border. Where is the coercive edge? How are you challenging Pakistan's strategic depth?" asks Lt General P.S. Mehta, former deputy army chief.

How many IBGs have been deployed in the western sector until now...Already deployed.

This is a correct statement.@Falcon.. How valid is this statement.. ? I was of the opinion that the Strike corps are not being re-structured.. and these strike corps would be the follow-on forces, once the IBGs make their gains...

Four at the last count.How many IBGs have been deployed in the western sector until now...

You mean the Strike corps ( 1 Corps, 2 Corps & 21 Corps ) too will be restructured into IBGs ? Kindly confirm ..This is a correct statement.

Nooo. They will remain strike corps. IBGs have been carved out of Pivot Corps and not from Strike Corps.You mean the Strike corps ( 1 Corps, 2 Corps & 21 Corps ) too will be restructured into IBGs ? Kindly confirm ..

Thanks...Retired.. Lt General P.S. Mehta is wrong in his assertion then... His statement got me confused..Nooo. They will remain strike corps. IBGs have been carved out of Pivot Corps and not from Strike Corps.

Russia is helping China with establishment of an early warning system to detect ICBMs aimed at it. Apart from the US & Russia, China will be the third country to possess this system. In the absence of such a system, how sure are we of prosecuting any war with Pakistan to retake PoJ&K given the chance it'd go nuclear? Any hints?Er.... Strike Corps already have IBGs as the model. Since 2015. The fully integrated model is sometime off anyways.

The IBGs are mini Strike corps and modelled as such.Thanks...Retired.. Lt General P.S. Mehta is wrong in his assertion then... His statement got me confused..

Russia is helping China with establishment of an early warning system to detect ICBMs aimed at it. Apart from the US & Russia, China will be the third country to possess this system. In the absence of such a system, how sure are we of prosecuting any war with Pakistan to retake PoJ&K given the chance it'd go nuclear? Any hints?

Our satellites can track the thermal signature of a launch. But honestly the time window from a launch to impact is pretty small.

I'd guess this has been gamed already. That in case Pak strategic forces get launch ready, our leadership will be probably be moved to secured shelters. ABM batteries will be on alert. That kind of thing?

This would imply we've eschewed pre emption. I don't think that's the case.I'd guess this has been gamed already. That in case Pak strategic forces get launch ready, our leadership will be probably be moved to secured shelters. ABM batteries will be on alert. That kind of thing?

Multiple scenarios?This would imply we've eschewed pre emption. I don't think that's the case.

A scenario where we cannot guarantee 100% success in preemption will have contingency planning in place.

Unpopular opinion - give the way Pakistan military works- they are sold on the use it or lose it concept and our capabilities, I dont feel we can ensure 100% launch prevention.

In the absence of such a system, how sure are we of prosecuting any war with Pakistan to retake PoJ&K given the chance it'd go nuclear? Any hints?

The hint is in the statement that I oft make - Pakistan is in no position to use its nukes anymore.

Could you elaborate on it ? I certainly don't think our military planners can mount a campaign to retake PoJ&K without factoring in the possible usage of N weapons by Pakistan and taking adequate precautions.The hint is in the statement that I oft make - Pakistan is in no position to use its nukes anymore.

When I posed the same question to PKS, he claimed the war would be waged & restricted to only J&K. When I countered him that this is precisely the thinking by Pakistan in 1965 which landed them in trouble & that there's a possibility we'd be emulating them thereby falling in the same trap, he reiterated his earlier stance.