The ‘QuadFather’: The Legacy of Shinzo Abe and the Quad

Trouble on the Horizon

Given their acrimonious history, it is perhaps unsurprising that the Japanese government was never as enamored by the narrative surrounding China’s “peaceful rise” as many of its Indo-Pacific peers were, at least initially. Many years before China began pressing its unlawful claims in the South China Sea, a game of military brinksmanship began to unfold in the East China Sea, near the Chinese-claimed, Japanese-administrated Senkaku islands.

[1] In 2003, the two countries began sparring

[2] over Chinese drilling efforts in the controversial Chunxiao underwater gas field whose reserves straddle the “median line” between Chinese and Japanese maritime claims. That year, Japan’s Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) also witnessed an important change: while China had been the top destination for Japanese ODA in the years prior, India overtook China in 2003 and has remained the largest recipient ever since.

[3]

In 2004, the Chinese government articulated a new maritime strategy

[4] in its White Paper that year, promoting the development of “far seas” defence capabilities while expanding the space for “offshore defensive operations.” That October, Chinese warships entered the waters around the disputed Senkakus and the following month a Chinese nuclear submarine

[5] was spotted entering Japan’s territorial waters near Okinawa.

Japan unveiled new defense guidelines

[6] in the same year, for the first time calling out China by name as Tokyo eased a longstanding ban on arms exports.

[7] The following year, Chinese warships organised a show of strength near the Chunxiao gas field, aiming their guns at a Japanese surveillance plane. The message,

[8] according to United States (US) Rear Admiral Eric McVadon, was clear: “We used to be inferior to you. Now we have to be taken seriously.”

In April 2005, several Chinese cities erupted in protests over news that the Japanese government had approved new junior high school textbooks which critics said downplayed the crimes of imperial Japan in the early 1930s. Some of the protests—which could not have proceeded without government acquiescence—turned violent, with countless Japanese businesses vandalised.

[9] Weeks later, then Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi visited India and signed a new joint vision statement titled ‘India-Japan Partnership in the New Asian Era’.

[10]

Amid another bout of tensions over the Chunxiao gas field, in July 2006 Shinzo Abe, a member of Japan’s parliament and the grandson of a former prime minister, published a book,

[11] Toward a Beautiful Country: My Vision of Japan. In it, he urged Japan to strengthen collaboration with Australia, the US, and, especially, India—a group of democracies cooperating to promote peace and prosperity across the region. Two months after the publication of his book, Abe was elected prime minister. Within weeks, US and Japanese officials were alarmed by a “wake up call”

[12] when a Chinese submarine surfaced within torpedo range of a US aircraft carrier operating near Okinawa.

This brief describes how Abe saw the trouble with China on the horizon, long before his contemporaries did. In July this year, Abe’s life was tragically taken by a gunman while he was giving a public address in Japan. Part of his legacy would be the strategy that he articulated to meet the China challenge, working tirelessly for over a decade to realise his vision for a ‘free and open’ Indo-Pacific protected by the region’s most capable democracies.

The Quad 1.0

Four months after Abe was first named prime minister in 2006, then Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Aso delivered a speech

[13] promoting the idea of an ‘Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’ across the region. He placed India at the centre, with Australia, Japan, and the US comprising the eastern flank, and NATO and Europe, the western flank. The following month, Abe welcomed then Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to Tokyo and the two upgraded the two countries’ relationship to a ‘Strategic and Global Partnership’.

[14] They also discussed holding a dialogue with “other like-minded countries” on “themes of mutual interest.”

In March 2007, Abe hosted

[15] a visit by then US Vice President Dick Cheney in Tokyo where the two discussed the idea of holding a quadrilateral dialogue with Australia and India. The idea was not entirely novel. In December 2004 the navies of the four countries were thrust into a collaborative initiative under unfortunate circumstances. A series of cataclysmic tsunamis generated by an undersea earthquake off the coast of Indonesia claimed hundreds of thousands of casualties

[16] across the Indo-Pacific. In the immediate aftermath, the four capitals coordinated humanitarian relief efforts as first-responders under the auspices of a regional ‘Core Group’

[17] while the international community scrambled to organise a more comprehensive aid effort.

Shortly after Abe and Cheney discussed the Quad, Japan was invited to join the India-US Malabar

[18] naval exercises, the first time the three navies would drill together. China’s Communist Party mouthpiece, the

People’s Daily pondered at that time: “It is absolutely not new for Japan and the U.S. to sit down and plot conspiracies together but it is rather intriguing to get India involved.”

[19]

In May 2007, mid-level officials from the four democracies held the inaugural meeting

[20] of a new Quadrilateral Security Dialogue on the sidelines of an ASEAN Regional Forum meeting in Manila. It was later described

[21] by Australian officials as an “informal meeting” that was “a natural partnership between countries which share values and growing cooperation” and “indicative of an interest in having exploratory discussions.”

As fate would have it, Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) suffered a crucial electoral defeat in July 2007, but Abe refused to step down. In October that year, Abe delivered

[22] an address to the Indian parliament titled “Confluence of the Two Seas” in which he laid additional foundations for his Indo-Pacific concept. He envisioned an “immense network spanning the entirety of the Pacific Ocean, incorporating the U.S. and Australia [with India and Japan]. Open and transparent, this network will allow people, goods, capital, and knowledge to flow freely.”

A few weeks later, the navies of the Quad countries assembled for the first time since the 2004 tsunami, this time joined by Singapore, for a special edition

[23] of the Malabar exercise. Eight days after the exercise, Abe resigned and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue soon unraveled almost as quickly as it began. In November 2007, Australian voters elected a Labor government led by a prime minister, Kevin Rudd, committed to a more conciliatory approach to China. Amid rumours of some discomfort with the Quad in Washington and Tokyo, then Australian Foreign Minister Stephen Smith and his Chinese counterpart Yang Jiechi held a press conference in early 2008. Smith announced that Canberra was no longer interested in the quadrilateral dialogue.

[24]

Perhaps the great flaw in the Quad 1.0 was neither its agenda nor membership but rather its timing. In 2007, China was still effectively marketing a soft-power offensive under a “hide and bide”

[25] strategy while the four democracies lacked consensus on the scope of the China challenge and the appropriate response. In all four capitals, influential interest groups remained committed to the engagement strategy

[26] that had long guided China policy, counseling

[27] against any initiatives that resembled a Cold War-era containment strategy.

To be sure, the China of the mid-2000s—of Chairman Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao—presented more of a paradox. The revolutionary fervour of the early Cold War had been replaced by technocratic leadership

[28] and export-led growth. Around the turn of the century, Beijing resolved

[29] the majority of its outstanding land border disputes amicably and joined a plethora of regional and international institutions while America and much of the world were preoccupied with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the Global War on Terror.

The great irony is that just as the sun was setting on the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the shadow of a new China—a more aggressive and more repressive rising power—was emerging in the twilight.

The Empire Strikes Back

As the Quad was disbanding in early 2008, the Chinese leadership was preparing to host the summer Olympics, an opportunity for Beijing to showcase China’s economic miracle to the world. The official charged with overseeing planning

[30] for the Olympics was a rising Party cadre recently promoted to vice president, Xi Jinping. Xi was elevated to the vice presidency in March 2008, coincidentally the same week the restive population of the Tibetan plateau erupted

[31] in violent protest on the anniversary of a major uprising against Chinese rule in 1959. Dozens of Tibetans were killed in the resulting security crackdown.

The unrest unnerved the Communist Party at a time when Beijing’s international image was already under duress. The crackdown in Tibet invigorated an existing campaign urging Western governments to boycott

[32] the opening ceremony of the Olympics to protest Beijing’s role in a brutal civil war in Sudan. The criticism, and the “partial boycott” that followed, generated a backlash in China and further fueled a wave of nationalist pride propelled by the dual impulses of “resentment and restoration.”

[33]

As significant as it was, the Beijing Olympics was eclipsed by an even more consequential event the same year, the global financial crisis.

[34] Originating in the US financial and housing markets, the worst global economic crisis in decades was by many accounts interpreted by the Chinese leadership as symbolic of an epochal power shift from one superpower in terminal decline to another reclaiming its position atop the global order. Dramatic predictions about the resilience of China’s economy and the fragility of America’s were eventually discredited but not before an important psychological threshold had been crossed.

One decade after the global financial crisis, China’s nationalist mouthpiece, the

Global Times, ruminated on its impact in heralding a “post-American era.”

[35] “The historical turning point of this era’s arrival [was] the global financial crisis that started from Wall Street in 2008,” it posited. “Due to great changes in the political, economic, ideological and cultural aspects of the world power balance, the end of the ‘American century’ has become a reality, and the international order’s adjustment is inevitable.”

In the years to follow, Chinese foreign policy assumed sharper, more assertive edges. In December 2008, a few months after the Beijing Olympics, the Chinese navy expanded

[36] the scope of new “maritime rights protection” patrols in the East and South China Seas, with Chinese military vessels accelerating patrolling around the Senkakus, a trend that would only increase in the years ahead. In March 2009, Chinese fishing and law enforcement vessels engaged in a handful of “reckless and dangerous”

[37] manoeuvres to harass unarmed US Navy surveillance ships in the Yellow Sea. One month later, China submitted its ‘Nine Dash Line’

[38] to the United Nations, unlawfully claiming virtually all of the South China Sea. Within weeks of the submission, a Chinese submarine collided

[39] with a US destroyer near the Philippines’ Subic Bay, damaging its underwater sonar array.

At a security forum hosted by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in July 2010, then Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi gave a “rambling 30-minute response”

[40] to a speech by US officials, declaring: “China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.” That September, Japanese forces detained

[41] a Chinese fishing boat captain that had rammed a Japanese Coast Guard vessel near the Senkakus, prompting the worst diplomatic row in years. China responded by temporarily suspending

[42] vital rare earth metals exports to Tokyo.

In 2012, a standoff

[43] between Chinese and Filipino naval forces over the disputed Scarborough Shoal prompted the US to mediate a deal in which both parties ostensibly agreed to withdraw from the standoff site and enter negotiations. Manila complied. Beijing did not, and has maintained a constant presence

[44] around the disputed rock since. The same year, the Senkakus again assumed centrestage when the nationalist governor of Tokyo offered to purchase

[45] the islands from a private Japanese citizen. Partly to pre-empt the governor from staging provocative acts on the islands, the Japanese federal government intervened

[46] to purchase the islands instead, sparking another crisis in China-Japan relations. With Chinese foreign policy already trending in a more aggressive direction, in November 2012 Beijing presented a new face to the world when the mild-mannered and technocratic leader of the Communist Party, Hu Jintao, was replaced

[47] by the confident nationalism of Xi Jinping and his ‘Chinese Dream’.

[48]

The Return of Abe

Just one month after Xi was named Communist Party chairman, Japanese voters returned Abe to power when the LDP swept

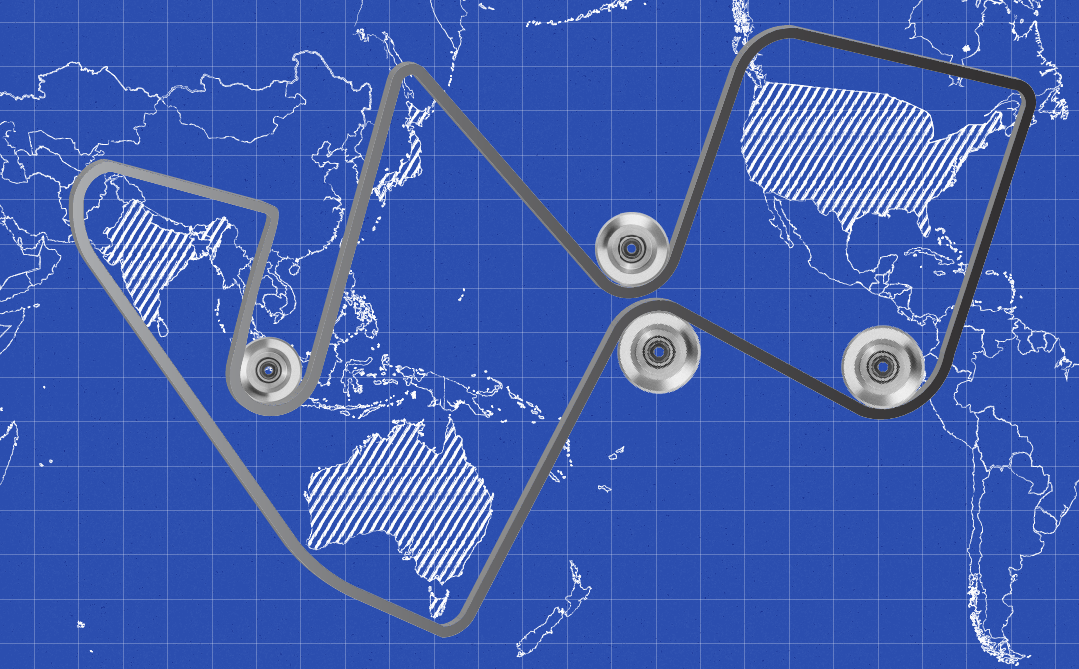

[49] national elections. In his first weeks in office, Abe repackaged his Quad proposal, calling for the formation of an Asian ‘Democratic Security Diamond’

[50] that would unite the four countries in defence of a rules-based order. “I envisage a strategy whereby Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S. State of Hawaii form a diamond to safeguard the maritime commons starting from the Indian Ocean Region to the Western Pacific,” Abe argued. He insisted that he was “prepared to invest the greatest possible extent, Japan’s capabilities in the security diamond.”

In 2014, Beijing declared

[51] an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the East China Sea. At the same time, in the South China Sea, Chinese dredging ships began piling sand atop seven rocks and underwater shoals, eventually creating seven artificial islands

[52] in the disputed waters of the Spratlys. After Chairman Xi publicly pledged

[53] not to militarise the outposts, China militarised

[54] the outposts.

The following year, Abe led efforts to adopt a less restrictive interpretation

[55] of Japan’s Constitution to allow the country to exercise collective self-defence, enabling it to support security partners outside of the immediate vicinity of Japanese territory. It was in the same year that India and the US welcomed Japan to become a permanent partner

[56] in the Malabar naval exercises after its periodic participation in the years prior. In March 2016, at the annual Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi, the head of US Pacific Command Admiral Harry Harris floated

[57] the idea of reviving a “quadrilateral venue between India-Japan-Australia and the United States.” He noted: “We are all united in supporting the international rules-based order that has kept the peace.”

With Chinese aircraft and “swarms”

[58] of marine vessels now regularly encroaching on the waters and airspace around the Senkakus, in August 2016 Abe further articulated his vision

[59] for the Indo-Pacific: a “union of two free and open oceans.” Japan, he argued, “bears the responsibility of fostering the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and of Asia and Africa into a place that values freedom, the rule of law, and the market economy, free from force or coercion.” Abe hoped this new Indo-Pacific construct would replace

[60] the outdated “Asia-Pacific.” According to former US deputy national security adviser Matt Pottinger, Abe “wanted people to zoom out and behold a much grander tableau that included India and that situated the youthful maritime nations of Southeast Asia, rather than China, at the conceptual heart of the region.”

In November 2016, the week Donald Trump was elected US president, Abe briefed

[61] Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on his new ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’ during a trip to New Delhi. Two weeks later, Abe became the first foreign leader to meet

[62] President-elect Trump. “Of all the allied leaders who visited the Trump White House,” Pottinger recalls,

[63] “none were more welcome than Abe.”

India and the Quad 2.0

The Trump administration, staffed with a healthy dose of China hawks in senior national security positions, quickly warmed to Abe’s Indo-Pacific and Quad proposals. The same was true in Australia, which by 2017 was embroiled in a paradigm-shifting debate over its China policy, including a very public reckoning over Chinese ‘influence operations’.

[64] Australia was not only open to the Quad and Indo-Pacific concepts, it quickly became their most enthusiastic advocate. Indeed, the Australian government had been the first to adopt the Indo-Pacific terminology back in its 2013 Defense White Paper.

[65]

India was another matter. In private, a decade later, Indian officials and experts were still quick to recall with distaste the abrupt dissolution of the first Quad in 2007-2008. India’s Non-Aligned legacy

[66] had bred an inherent skepticism of Western military alliances and counseled caution when dealing with China. The sentiment began to change under the government of Narendra Modi, elected in 2014. India-US defence ties were thriving

[67] as the two began concluding long-pending foundational military pacts. By contrast, Chinese incursions

[68] and prolonged confrontations along the disputed China-India border were growing more frequent. Unusually, India emerged as the earliest and most vocal critic

[69] of Chairman Xi’s multi-billion dollar, flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), part of which traversed Indian-claimed Kashmir. For New Delhi, however, reviving the Quad was likely still a reach.

Then, in the summer of 2017, Chinese military engineers began constructing a road in an obscure corner of the Himalayas where the borders of India, China, and Bhutan meet on the Doklam plateau. The Indian military intervened

[70] to halt the road’s southward expansion toward India’s vulnerable “chicken’s neck,”

[71] prompting a tense, months-long standoff replete with threats of war from Chinese nationalists.

India had seen enough. In August 2017, as the Doklam crisis was unwinding, then US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson discussed reviving

[72] the Quad with the foreign ministers of Australia and Japan on the sidelines of an ASEAN forum in Manila. He then publicly endorsed

[73] the idea in an October speech in which he also embraced

[74] Abe’s vision for a “free and open Indo-Pacific region stretching all the way [from] Japan to India.”

In October, US Defense Secretary James Mattis traveled

[75] to India and, within days of returning to Washington, signaled for the first time that the US harboured serious concerns

[76] about China’s BRI: “In a globalized world, there are many belts and many roads, and no one nation should put itself into a position of dictating ‘one belt, one road.” India had effectively won over the Trump administration. Australian officials began airing their own concerns

[77] about the BRI a few days later.

The same month, days after the Japanese electorate granted Abe a new mandate, Tokyo formally proposed reviving the Quad. The idea was backed

[78] by the Trump administration two days later. Unlike in previous years, when Indian officials balked at loose talk of the Quad’s reconstitution, a Modi government spokesman signaled approval:

[79] “India is open to working with likeminded countries on issues that advance our interests and promote our viewpoint.”

In November 2017, nearly a decade after it first collapsed, at nearly the exact same venue it began (on the sidelines of ASEAN-led meetings in Manila), the Quad was reborn.

[80] The Quad 2.0 has flourished since.

[81] Originally held at the working group level, Quad meetings have since been upgraded to the level of foreign minister and secretary of state and, most recently, leader-level summits. In 2020, the four navies again began conducting joint naval drills

[82] under the auspices of the Malabar exercise.

Today, the four countries meet regularly to discuss cooperation on pandemic relief, emerging technology, climate change, and maritime security. They have held counter-terrorism discussions and exercises and issued joint statements.

[83] A new Quad tech network

[84] promotes collaboration among think tanks and research institutes in the four countries. A new Quad fellowship

[85] programme will develop a network of science and technology experts collaborating in the private, public, and academic sectors of the four countries.

What then is the Quad today? In its current form, the group is not a traditional military alliance but a minilateral coalition of like-minded partners pursuing functional cooperation to advance shared interests. As this author has previously argued,

[86] the Quad is best seen as:

a symbolically and substantively important addition to an existing network of strategic and defense cooperation among four highly capable democracies…For now, and by design, it remains a malleable and agile coalition, offering its members flexibility in how they tailor the group’s agenda and scope. At this point, it’s less important what the Quad does than what it signals and symbolizes, a weather vane for the four democracies’ threat perceptions vis-à-vis China. The true value of the group lies in its potential, the foundations being laid, and the ability to restructure the scope and agenda in response to changing threat assessments.

Conclusion

Long before his contemporaries, Shinzo Abe was concerned that China’s rise would take a more ominous and nationalist turn. He feared China would pose unique and escalating challenges not only to Japan’s territorial integrity but to the regional order responsible for an extended bout of peace and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific.

Abe believed a challenge of this magnitude would necessitate thickening the already substantial bonds between Australia, Japan, and the US. Most importantly, it would require enlisting India, the only true demographic counterweight to China and what is today the country with the world’s third-largest defence budget. For Abe, these four democracies had something important in common: the requisite will and capabilities to defy Beijing, to resist economic and military coercion, and defend their sovereignty and territorial integrity. From a position of strength, the four countries could collectively articulate a positive vision for the region, provide public goods, and promote a regional order based on rules, rather than might.

An early attempt to realise this vision in 2007 produced a novel Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and Quad-plus naval exercise. Domestic politics forced Abe from power soon after but he never wavered from his vision. As the challenge from China grew more acute, he continued advocating, and providing the intellectual foundation, for the revival of the Quad and the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy.

When developing economies in the region sought alternatives to China’s BRI, Abe’s Japan was there to offer ODA. When an erratic Philippines president wavered on his commitment to his country’s alliance with the US, Abe flew to that president’s hometown to persuade him otherwise. When Indian officials expressed reservations about the Quad and Indo-Pacific, Abe was on the line to reassure them.

When China’s rise prompted the region’s most powerful democracies to adopt more rigorous balancing strategies, Abe constructed the framework and showed them the path forward. At home, Abe has secured his legacy as Japan’s longest serving prime minister. Yet, as this brief sought to outline, his foreign policy legacy may prove even more consequential.